You can be forgiven for thinking that the city of Silay in Negros Occidental is merely the place you land in to get to Bacolod City, which is generally the top draw for tourism of the province.

Driving out the Bacolod-Silay International Airport, you are treated to kilometers and kilometers of rice and sugar fields – it took 10 minutes of non-stop driving for me to finally see a modern building. Categorized as a 3rd-class municipality, you would be disappointed if you visited Silay with the intention of shopping or seeing modern architecture.

What Silay is well-endowed with on the other hand, is culture and history. It is after all referred to as the “Capital Artística de Negros” or the Artistic Capital of Negros [Island], the Spanish translation of that nickname is no mistake either – it is the centuries-old colonial-era structures that form the city’s identity.

It was first settled in 1565 by soldiers loyal to the Spanish explorer, Miguel Lopez de Legazpi. It wasn’t until 1760 that it was formally recognized as a “pueblo” or town by the colonial officers of the day, and by then European sugar barons eventually occupied the city establishing their own sugar plantations.

The indigenous population of Silay was granted as an “encomienda” to Cristobal Nuñez Paroja, one of Legazpi’s men, in 1571. An encomienda is a mode of indentured servitude where the Spanish Crown “grants” the receiver the benefit of the labour of the native population of a given community, mainly as a form of reward for service to the Spanish Monarchy.

After centuries of living under the oppressive system, the agricultural labourers of Silay – mostly those working in “haciendas” or sugar plantations – staged an uprising against their colonial masters on the 5th of November 1898, culminating what is now remembered as the “Cinco de Noviembre Revolution”.

It was a bloodless revolution, the hacienda workers of the city gathered in a street (presently called Cinco de Noviembre) and began marching towards the Spanish garrison. The local Spanish guard commander, Lt. Maximiano Correa, was terrified by the sheer number of the workers and eventually surrendered without a single bullet fired.

I visited the commemorative marker of this often-forgotten historic event at the exact street where the sugar plantation workers assembled, it is now called Cinco de Noviembre Street in memory of the event.

The city is full of heritage houses as well, these are the ancestral homes of the pioneer European families of Negros Occidental and are behind Silay’s current standing as a leading sugar producer in the Philippines. There are scores of these heritage spots all over the province, but the vast majority of which are located in Silay itself – in fact the city has the second most number of heritage houses after Vigan, Ilocos Sur.

During my brief tour of Silay, I visited three of these houses. One was the “Balay Negrense“, which I covered in this blog a few days ago, and belonged to the French sugar baron Yves Leopold Germain Gaston.

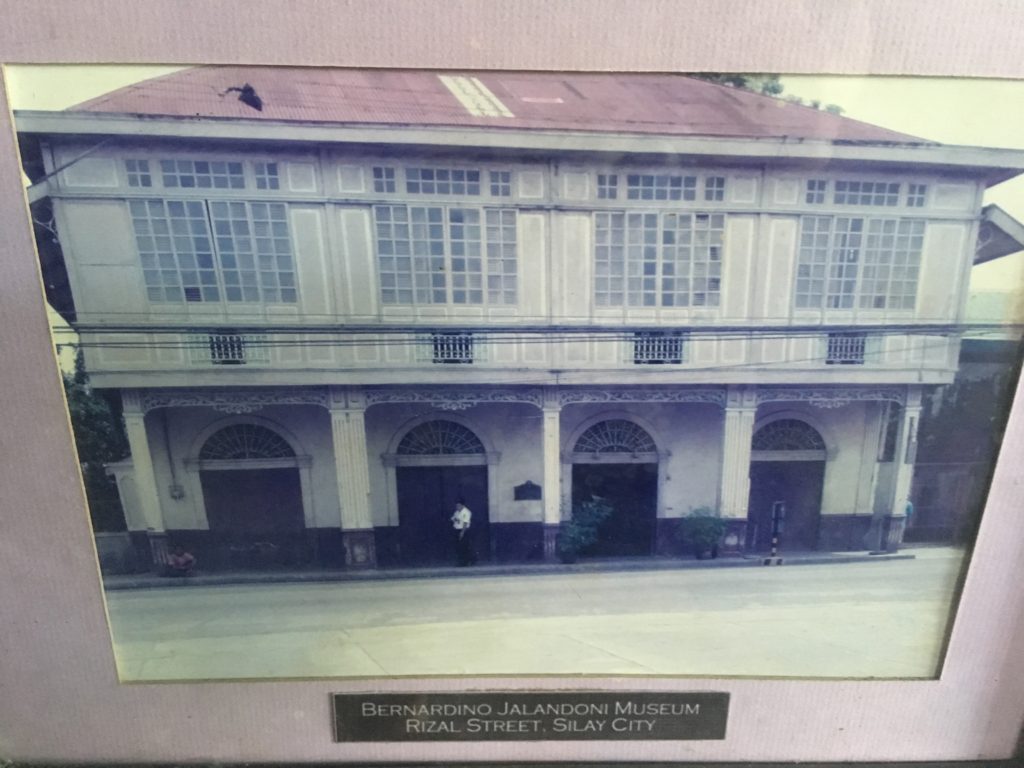

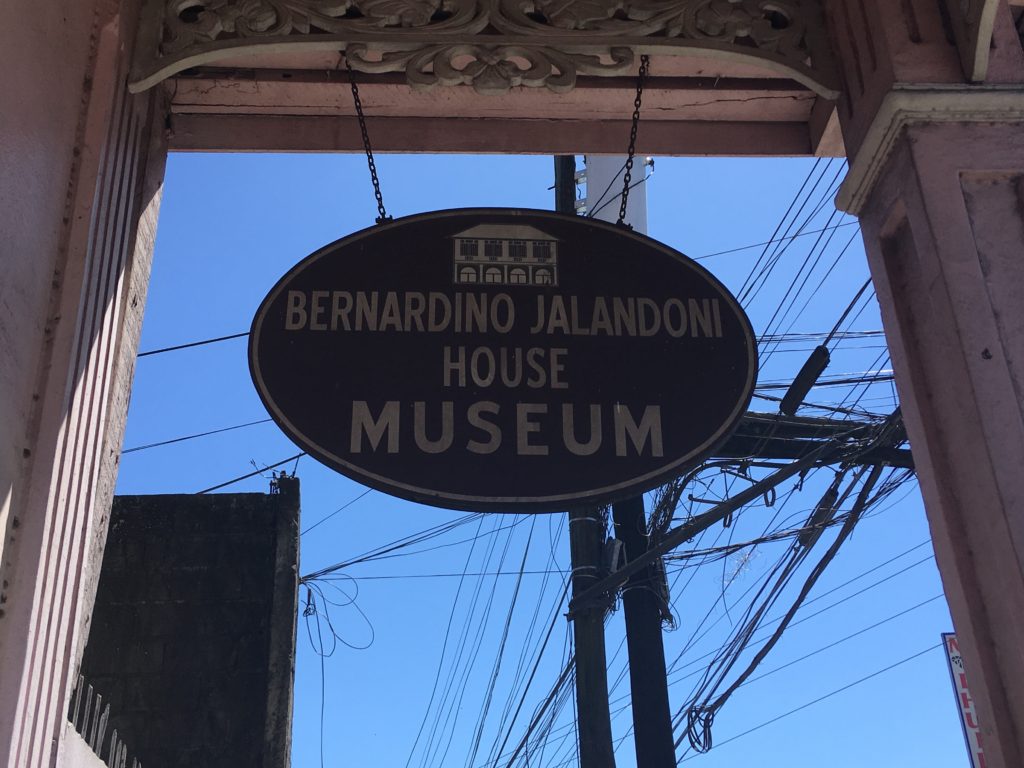

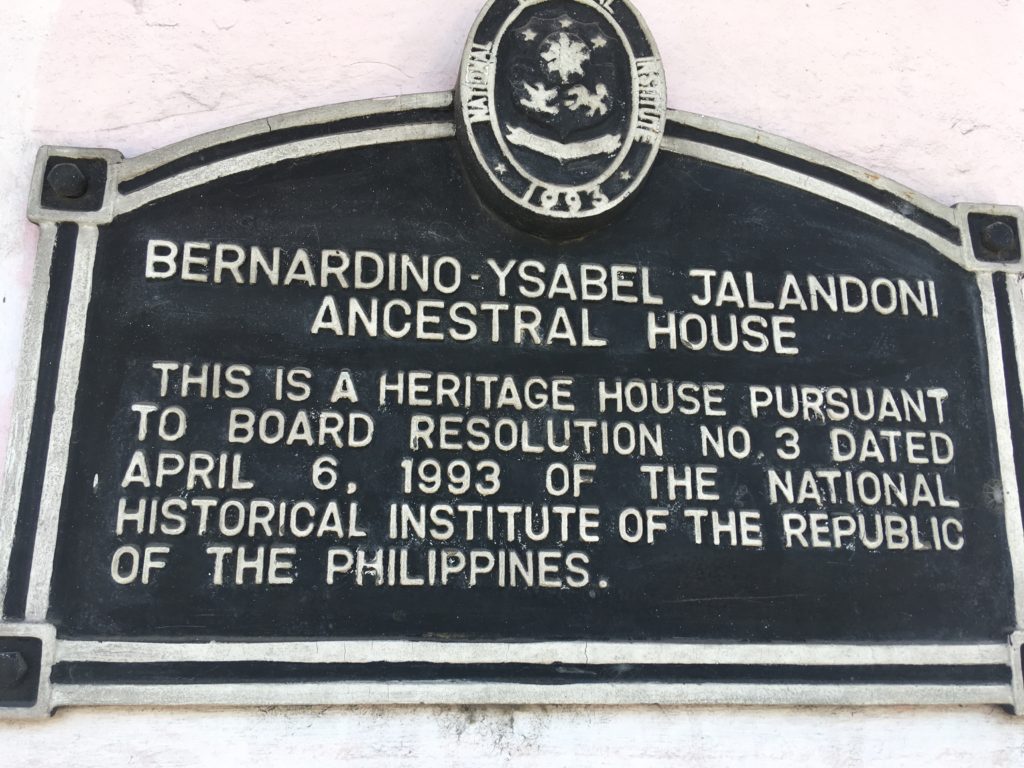

Another of these rich capitalists with European lineage who settled in Negros Occidental, were Don Bernardino Jalandoni and his wife Doña Ysabel Lopez Ledesma, who built and inhabited what is now the “Pink House” or the “Bernardino Jalandoni Museum” in Silay.

It is a house made of stone that was typical of wealthy families during the Spanish period, and the interior of the house is also adorned with opulent materials such as embossed steel trays made in Hamburg, Germany and various antiquated furniture shipped directly from Spain.

Most of these features have been well-preserved by the Silay Heritage Foundation, which have taken on the responsibility of maintaining the historical site. Entry to the museum will cost you a meager ₱60, and a tour guide will take you around the house and narrate the history of the place.

The Jalandoni House also accommodates cultural and artistic events, these include art exhibits and culturance dance presentations. While it is commonly referred to as the “Pink House” due to its pink painted exterior, this was only a modern addition and was done to make the house distinguishable from other heritage houses in Silay.

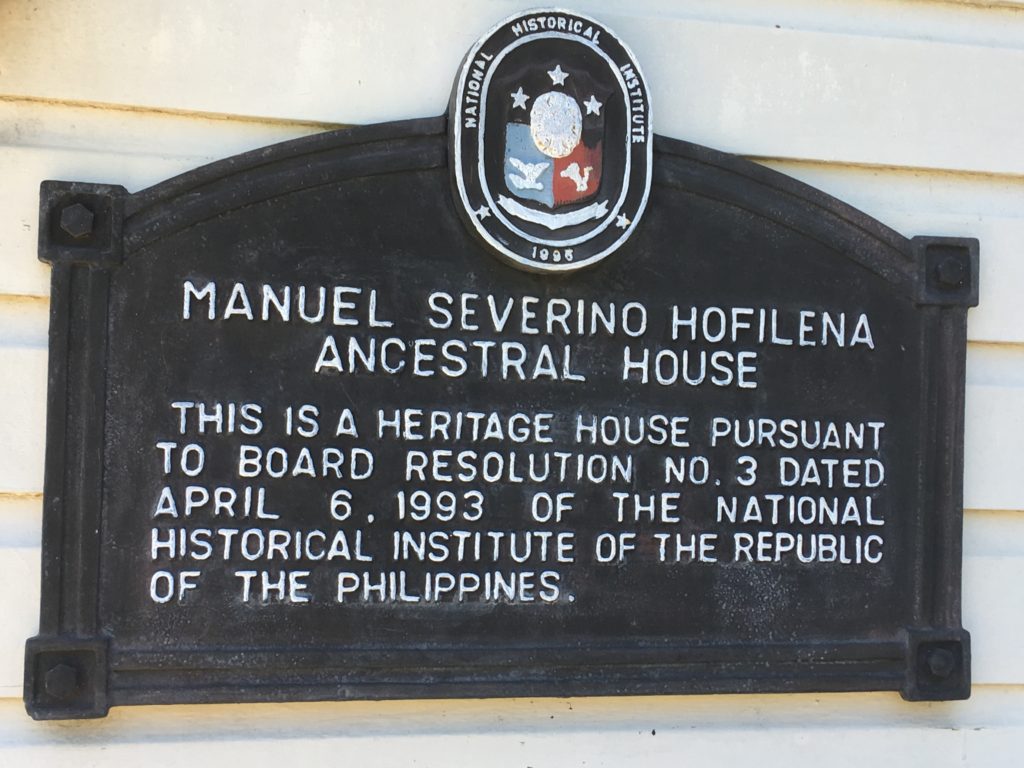

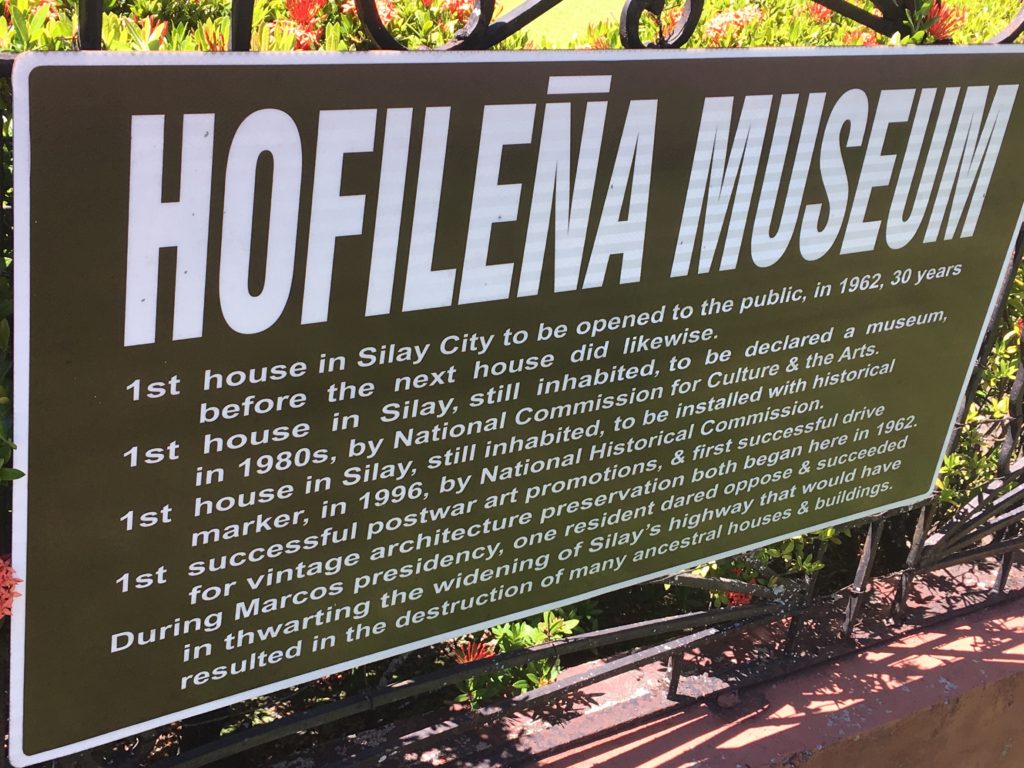

A ten-minute taxi ride will take you to another heritage site, the Hofileña Ancestral House located in Cinco de Noviembre Street. What makes this heritage site different from the rest is that one of the original inhabitants of the house, Ramon Hofileña, continues to reside here until this very day.

It was his father, the late Manuel Severino Hofileña, who commissioned the construction of the house in 1934. The age of the house makes it relatively younger than the other 30 heritage houses in Silay, it also means that the home was built during the American colonial era and not the Spanish-era.

While it is a product of the American period, the family traces their lineage to Spanish origins. The house itself is also conspicuously Spanish, particularly its architecture and interior design.

Its roof is of classic steep and wide eaves, unlike the galvanized iron sheets that have been the popular roofing material in Spanish-era Manila. The wooden surfaces of the house are made of “balayong” or ironwood, an in-demand building material at that time due to its invulnerability to termites.

The curator of the house, Ramon Hofileña, is an avid patron of the arts and you can see his vast collection of books, artworks and antiques in the heritage site. The ground floor sala or living room leads to a smaller room, which serves as his private library and where a treasure trove of rare, antiquated books are kept.

According to my tour guide, the world’s first pocketbooks are kept in the premises. The rationale for the smaller-sized books is to provide reading materials that were portable for American soldiers during World War II.

Several of the books in the library were penned by Ramon himself, the room also features a glass case containing souvenir items from his travels overseas. These souvenir items include a Russian babushka doll, a porcelain figurine of a pair of clogs from the Netherlands and a wood-carving of elephants from Kenya.

There are also highly-valuable items inside the house, which explains the security personnel you will see in the vicinity. There is are 3,000-year old Ming dynasty porcelain wares displayed as part of the tour, and a 200-year old German Steinweig piano.

The second floor of the house is even more strictly secured, as you are forbidden to use any gadgets – especially to take photographs – in that area. This is because the upper level of the Hofileña house is also the art gallery, where you will see Ramon’s vast collection of artwork from legendary Filipino painters such as Felix Resurrecion Hidalgo, Fernando Amorsolo and Juan Luna.

Due to the personal nature of the exhibits, there are occasions when Ramon Hofileña himself conducts the tour for visitors. During my visit, he was resting in the ground floor living room while the tour was ongoing.

Just like the Jalandoni Museum, the Hofileña heritage house also has a ₱60 entrance fee which leads me to believe that all the heritage sites managed by the Silay Heritage Foundation charge the same fee – most probably a basic charge to cover running costs.

I can’t imagine the National Historical Institute nor the Silay Heritage Foundation to be brimming with funds, yet the heritage houses I visited were all in decent condition. It goes without saying that these culture & arts organizations deserve praise for their efforts, and paying the very meager fee is definitely worthwhile.

Those with a basic knowledge of Philippine history may point to Cavite or Cebu as the cultural havens of the country, completely oblivious to the fact that the Negros provinces were the location of numerous defining moments in our country’s history. The first time the Philippine flag was waved in the country happened in Silay City, and for a brief time the Negros Republic – formed by Filipino nationalists – ended Spanish colonial rule over Filipinos.

My visit to Silay was certainly an eye-opening experience to our country’s past, particularly because the well-preserved heritage sites made it feel like I was living in those times myself. So while Silay City may not be able to boast of top-notch beach resorts or high-end shopping malls, you will be able to indulge yourself in a beautiful historical narrative that will help shape your understanding of our origins.