The Regional Economic Development Minister Shane Jones put his foot down and announced a plan to put beneficiaries into work, recently. The move was erroneously called “Work for the Dole”, but is in reality a plan to stamp out unemployment in regional New Zealand by enticing those receiving the unemployment benefit to work minimum wage, community-based jobs.

Those jobs are most likely linked to Jones’ other initiative of planting one billion trees in the regions, thus we should expect to see unemployed New Zealanders going out to plant trees as part of this work scheme. The plan was targeted by critics, calling the plan “demeaning” to the unemployed and some even compared it to “slavery”.

Yet what can be more demeaning than to be able-bodied yet not in employment? A feature article published recently outlined the difficulty of finding work in the Northland region, the author intended it to be a counter to Jones’ work scheme plan. Yet the grievance aired by the beneficiary – a teenager named John Smith – gave the best defense for the said plan, there are not many private employers hiring workers in the economically troubled region so the state creating jobs would actually help his plight.

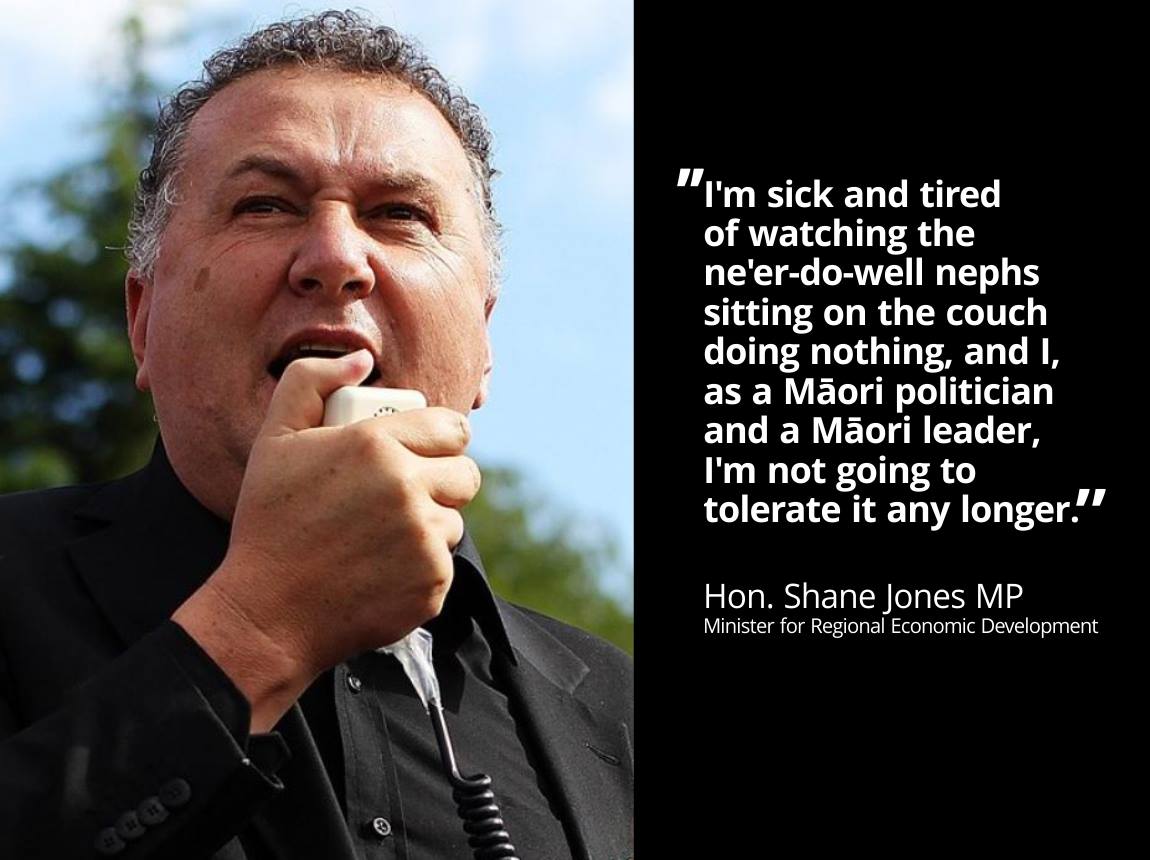

Smith also echoed the concerns shared by the Hon. Shane Jones, he admits that many people his age who are out of employment resort to illegal activities such as drug abuse and vandalism. The Minister wants his initiative to counter the allure of gangs to unemployed youth, saying he did not want his “ne’er-do-well neph[ews] fall victim to the gangs”. His sentiments are further backed by a Parliamentary research paper published in 2009, which states that “gangs more likely to grow in depressed or disorganized communities” and drawing a link between youth delinquency and economic deprivation.

If the state can provide these NEETs (not in employment, education or training) with meaningful tasks to fulfill, not only will they be too preoccupied to partake in criminal activities but they will also see their disposable incomes increase and will then create a flow-on economic effect to the rest of the local economy.

It is also a well-known fact that rural New Zealanders are disproportionately affected by mental health problems, with scarce employment opportunities and inaccessibility of mental health services the most likely culprits. By producing economic activities for the unemployed in the regions, Jones’ programme stands to help stymie mental health problems as well. Research also informs us that inactivity can worsen depression among those who suffer from it, hence by performing physical activities we prevent depressive episodes from happening.

Jones’ detractors point out that his plan was made off-the-cuff and did not have the backing of New Zealand First’s coalition partner, the New Zealand Labour Party. However, the Prime Minister and the latter party’s leader Jacinda Ardern has already stated that she would support a “work for the minimum wage” programme which is precisely what her Minister envisions to produce. In that televised interview with Q+A, Jones clearly stated that the beneficiaries who will be targeted with this policy will be paid a minimum wage where necessary.

At the same time, in November 2016 the Labour Party also presented a similar policy they labelled “Ready for Work”. This policy according to a factsheet on their website wants “all young people, who are able, will be in work, training or education.” Many opponents of Jones’ plan state that it is unethical to force beneficiaries to work, but they do not realize that Ardern’s party also plans to do the same.

It should be expected that such a plan would cop out a barrage of criticisms: it is bold and politically risky, but is definitely necessary. The Hon. Shane Jones would have undoubtedly predicted this initiative would be unpopular, which is why he deserves all the props for pushing it.