What is a fate worse than death? It can be argued that a person suddenly disappearing is more taxing than merely dying. By vanishing without a trace, that person’s surviving family is denied closure – they don’t know what had happened to their loved one.

This is perhaps why enforced disappearances is such a common tool used by tyrannical governments to intimidate their political opponents and crush dissent. Extrajudicial killings might be effective in silencing your rivals, but seeing them disappear inflicts further damage to the victim’s bereaved kin also.

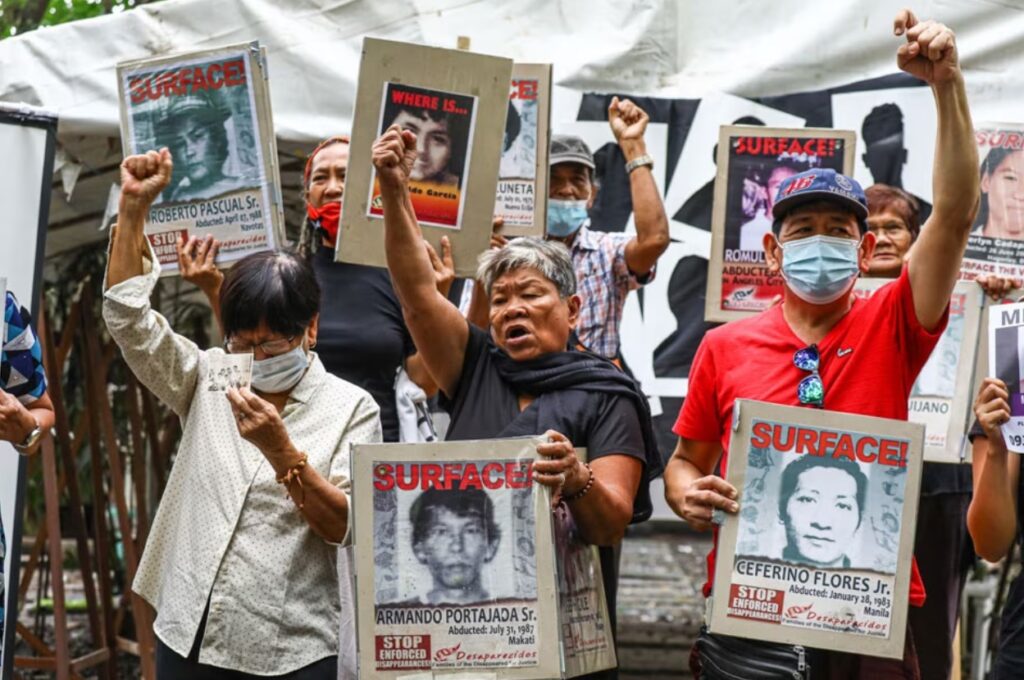

The Philippines is no stranger to enforced disappearances. The UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, which assists families find victims of enforced disappearances or desaparecidos, has documented at least 1,301 cases that remain unresolved in South-East Asia. Of that number, half are from the Philippines alone.

The biggest uptick in desaparecidos in the Philippines occurred during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos Sr. A total of 926 activists, trade unionists, and other political dissidents went missing by the time he was deposed in 1986.

Many of those enforced disappearances would remain unsolved to this day, which is painful enough for the families those victims left behind. Making things worse for them however, is that the late dictator’s son and namesake – Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. – has assumed the presidency since, returning the Marcos family to power in the Philippines.

Taking a page out of his father’s draconian playbook, there have been further cases of enforced disappearances under Marcos Jr. According to human rights group Karapatan, there have been eight recorded cases of enforced disappearances during the first year of Bongbong Marcos’ term.

Under President Rodrigo Duterte’s regime, Bongbong Marcos’ predecessor, there were at least 20 activists who went missing. This would be dwarfed by the number of desaparecidos under President Gloria Arroyo, which totaled to 206 over a nine-year term.

Putting those statistics aside, we must avoid reducing the desaparecidos to mere numbers. These are lives lost, families torn apart, and important voices in our democracy unjustly silenced.

These desaparecidos include Elizabeth ‘Loi’ Magbanua and Ador Juat, two labor organizers who were abducted by suspected state forces on May 3, 2022. In September that year, the judiciary held the Philippine Military liable for their disappearance and ordered that they be surfaced. It has been a year since that court order, yet Loi and Ador’s families are yet to be reconnected with their missing kin.

Last April, Gene Roz “Bazoo” de Jesus and Dexter Capuyan went missing after going for a medical check-up in Rizal province. The two were staunch indigenous rights activists and because of their activism, the Philippine Military had previously accused De Jesus of being a combatant with the New People’s Army (NPA). Human rights groups believe the two are currently under military custody.

Another indigenous rights activist, Steve Tauili, also went missing momentarily but was fortunately resurfaced unharmed. Tauili, who has led protests against the building of hydro-electric dams in his tribe’s ancestral lands, disclosed that he was mauled and abducted by five armed men while on his way home. It can only be surmised that these men were state agents.

Tauili is fortunate to be among only a few desaparecidos to have been resurfaced alive. When developmental worker Elena Tijamo went missing in 2020 she would only be seen again a year later, unfortunately already deceased.

The Cebu-based activist worked with peasant communities, providing free legal aid in their disputes with big landowners. It came as no surprise that Tijamo would find herself in the cross-hairs of the state, which patronizes large comprador landlords.

Analyzing the profiles of individuals that have been disappeared, we can see a pattern: activists who staunchly pursue their advocacy are targeted. This further adds credence to the claim that enforced disappearances are a tool which tyrannical governments use to eliminate dissent.

Among the desaparecidos are indigenous peoples fighting to preserve their ancestral domain, labour organisers fighting to provide better wages for low-income workers, or developmental workers helping impoverished farmers who lock horns with large land-owning families.

These are people who fight back against a Philippine government that promotes the interests of the wealthy, powerful few and because of that, the state uses its armed forces to crush these dissidents.

This is why it is important to remain steadfast in the fight to end all enforced disappearances, and to surface those who have been disappeared. To demand justice for the desaparecidos and to remain vigilant to ensure there are no more means to preserve our democracy and prevent state capture by a wealthy elite.