The influential Irish-American labour union organizer Mother Jones once declared: “the rough hands which create the wealth of the world should be allowed to share it”. As an activist for the working class, she tirelessly fought for the ideal that the labourers who toil to generate prosperity in society should be valued with fair pay, safe work conditions and be treated with dignity.

Jones passed away in 1930, but nearly a century later the fight she waged is still as relevant as it was during her time. At present, manual labourers continue to fall victim to exploitative practices including being paid less than what’s fair, not being afforded basic meal breaks and having no security of tenure.

These cases may be more prevalent in developing countries, but even among OECD nations these injustices still occur. In New Zealand, cases of workers’ exploitation is rampant among Filipino builders sustaining an infrastructure boom in Auckland and a post-earthquake rebuild in Christchurch.

With an overheating property market, Auckland desperately needs more residential areas and the Government already announced a colossal plan to build 10,000 houses in ten years in the region. The sheer scale of the project entails a large workforce, the problem is compounded by a shortage of tradespeople in New Zealand – which forces construction companies to look overseas.

Auckland’s transport infrastructure is also in the process of an overhaul, with the Central Business District (CBD) being fitted with its first subway network and bus rapid transit (BRT) systems being introduced to its suburbs as well.

Meanwhile, the rebuilding of Christchurch has encountered many hiccups related to government policy, funding and the manpower to meet the demands of the construction process. A large number of Filipino builders have already been recruited overseas to fill these gaps and yet there continues to be delays in the project related to labour.

These realities make the work that Filipino builders do extremely important, yet the value of their mahi is not reflected in the way they are treated.

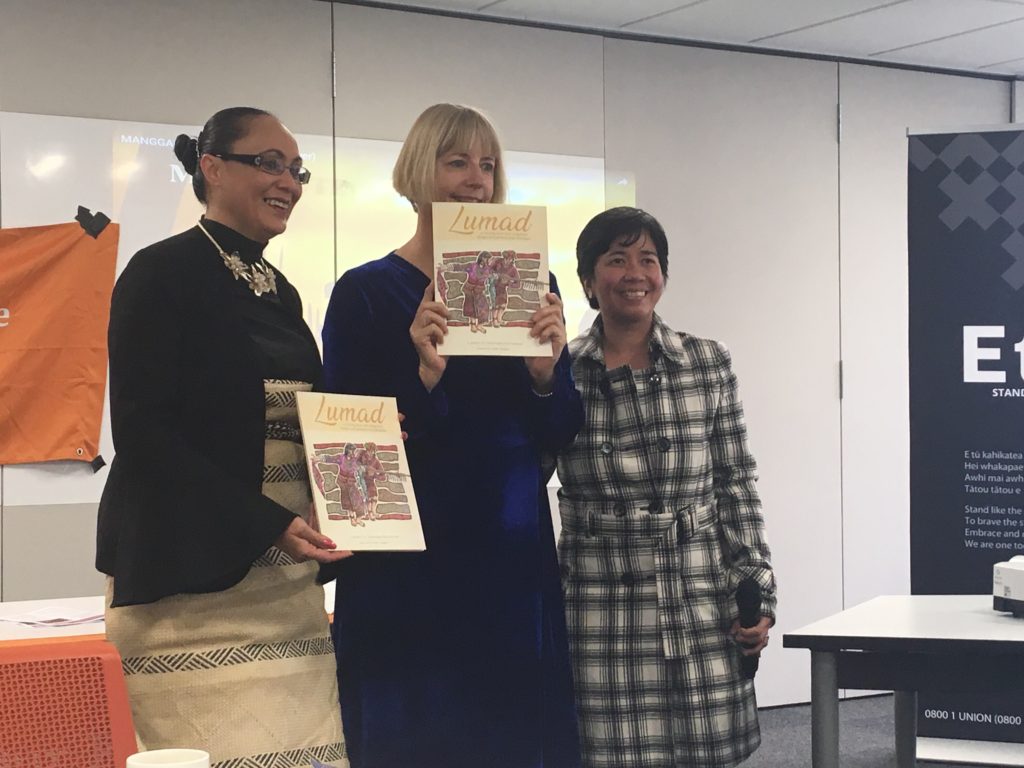

In August, an investigative report conducted by lawyer Catriona MacLennan for the E tū labour union revealed the shocking extent of exploitation suffered by these migrant Filipino builders. The injustice these workers suffered was no longer restricted to several isolated cases but rather a normalized culture of abuse towards migrant workers.

In her report, which surveyed 42 Filipino migrant builder in both Auckland and Christchurch, MacLennan did not find a single respondent who was paid the average hourly wage for builders in New Zealand.

When the average pay was $29/hour, the most a Filipino builder received was $28/hour and that was only one respondent. Majority of the survey respondents were paid between $19-$25/hour for doing the same work.

This arrangement raises questions: is a salary not a reward for the work one performs? If a Filipino builder makes the same contribution as a Kiwi-based worker, why should he not be paid the same as workers of other origins given they provide the same value?

For many of these Filipino builders, they aspire to live permanently in New Zealand and bring their families with them who have been left back home in the Philippines. The tragedy is that the minimum salary threshold for the skilled migrant category is $23.49/hour as of 2017, for those who earn below that threshold they don’t even qualify to become permanent residents in the country.

Effectively, these migrant workers can build the essential infrastructure that New Zealand requires and can still be discarded easily. Their job security is made more precarious by the fact that they are only in the country on one-year work visas, and have no guarantee of an extension.

The Labour Party – part of the ruling Coalition Government – campaigned to remove 90-day trial periods to improve job security for workers. They argued that allowing employers to lay-off workers without any substantial reasons after ninety days makes workers insecure about their employment status.

Surely, that Party can apply the same rationale to help these migrant workers stuck on one-year visas?

Faced with unfavourable odds, these Filipino builders are also fleeced for what pittance of an income they receive by “pastoral care” providers. MacLennan’s report found that some paid as much as $400 a week to these pastoral care companies to receive basic privileges such as driver’s license assessment tests and use of a work vehicle.

Pastoral care providers directly docked the pay of these migrant workers, which left some of the survey respondents with as little as $10/week to spend on food and other basic needs. The practice pushed these Filipino builders to rely on food banks and the generosity of concerned individuals to sustain themselves.

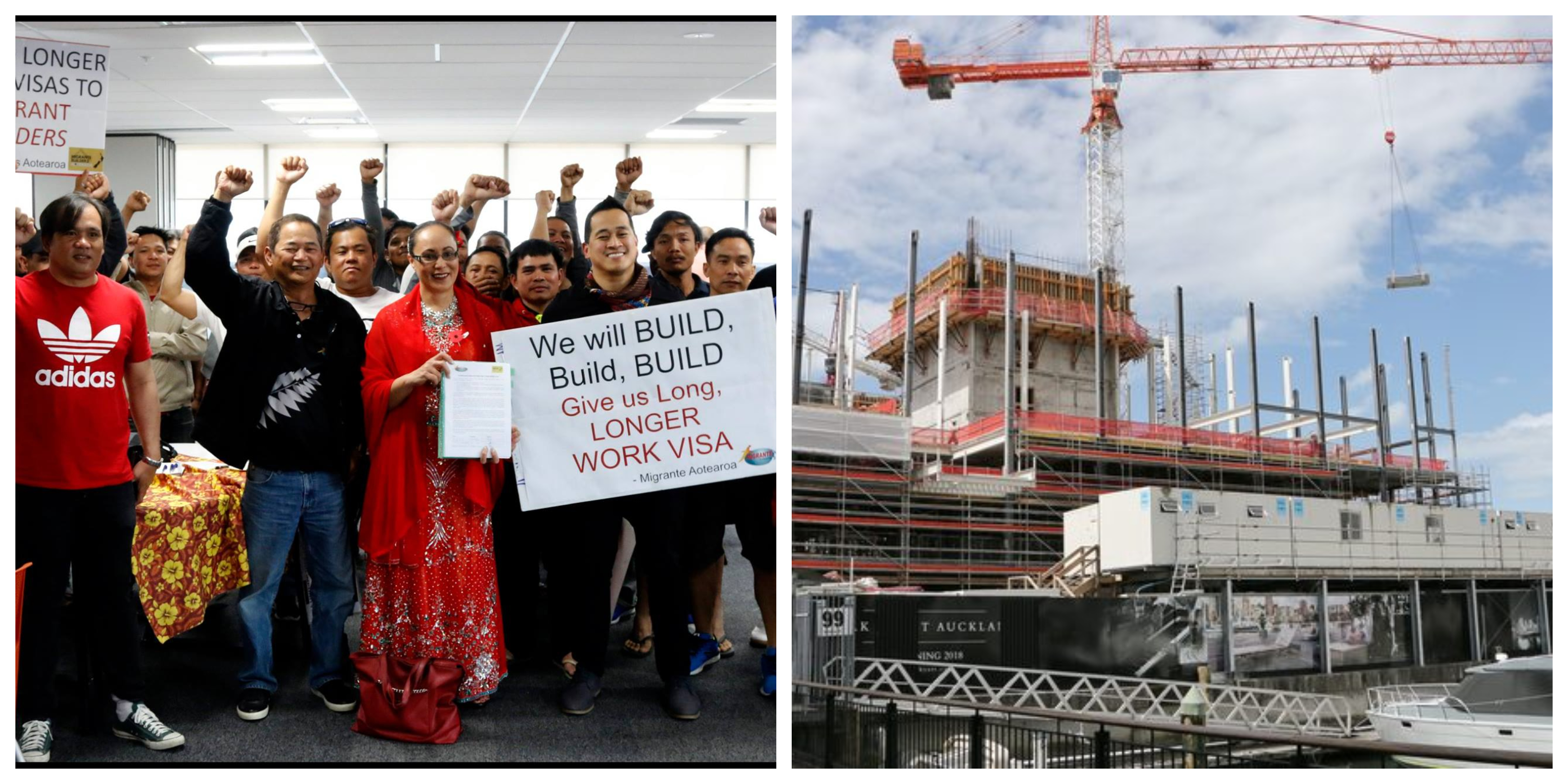

Having had enough of the status quo, builders under the Migrante Builders Union presented a petition asking for equal pay, longer visa periods and the regulation of pastoral care providers to the Government this past weekend. The Crown was represented by the Hon. Jenny Salesa, Minister for Building and Construction, who formally received the petition.

The petition can be viewed online at http://www.together.org.nz/building_our_homes

The outcry essentially tells the Government that if their infrastructure projects are important, then the workers who build the infrastructure are just as important also. Therefore, it is only just that they are given security of tenure – with 3-year work visas rather than one year visas, being paid equally with their Kiwi counterparts and providing oversight to dubious pastoral care companies who fleece them of the little salary they receive.

If successful, the migrant workers will be free of undue stress from worrying about the future of their employment and will also become more productive with better pay and living conditions. The decision should be a no-brainer for the government: the success of their pet projects hinges on the people that will oversee the completion of those projects, this makes them just as valuable as the project itself.

Hi ,can you help me mam/sir.