Last November, radio broadcaster Juan Jumalon – also known as “DJ Johnny Walker” – was shot dead by an assailant who entered his home studio during a live broadcast.

In March, Olongapo City news anchor Rowena Quejada went missing after being abducted by armed men, donning bonnets, while covering the demolition of shanties in Angeles City, Pampanga.

In 2018, several websites belonging to activist organizations were targeted by relentless Distributed Denial of Services (DDoS) attacks and also received shadow-bans on its social media accounts.

The RSF stated that the Philippines is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for journalists, adding that “impunity for these crimes is almost total.” Such a verdict is not exaggerated, after all, the country was named the “most dangerous place in the world” for journalists in 2009 by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

The risk in the profession increases exponentially among progressive or left-leaning journalists, finding themselves targeted by state forces after being accused as members or supporters of the communist rebellion – a practice known as “red-tagging”.

Members of the College Editors Guild of the Philippines (CEGP), have been harassed by state forces due to their involvement in protest actions and rallies. Student journalists have been summoned by the military, together with their parents, for no apparent reason other than to interrogate them about their activism.

Such tactic is designed to intimidate young journalists from exercising their democratic right to protest. The National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP), the trade organization representing journalists in the country, have also seen many of its affiliate-organizations face similar harassment and even acts of violence.

Ronalyn Olea, the NUJP’s secretary-general, was publicly accused of being a collaborator with the underground communist rebellion, by another media outfit allied with the former government of President Rodrigo Duterte. Such an accusation is extremely dangerous in the Philippine climate, given that journalists have been killed for the same reason.

One example is radio broadcaster Percival Mabasa, known by his pseudonym “Percy Lapid”, who was shot dead near his home in Manila in 2022. A vocal critic of the Duterte administration, Mabasa was a known anti-corruption crusader who had received threats throughout his career – but finally met his end once he criticized the Philippine government at the time.

Another activist-journalist with the NUJP, Frenchie Mae Cumpio, was also arrested by the military in Leyte province that year. The journalist with Tacloban-based Eastern Vista was arrested in a raid of what the military alleged was a “communist safehouse”.

There have been no concrete evidence presented to Cumpio’s defense to justify her arrest, yet up to this day – four years after her arrest – she continues to be under the custody of the Philippine military; the youngest detained journalist in the world.

Acts of violence and intimidation are not the only instruments used by the state to suppress journalistic freedom. Progressive media outlets have also been targeted by cyber-attacks, taking down their websites or shadow-banning its social media accounts for no apparent reason.

In 2022, in the final days of the Duterte presidency, the government ordered internet service providers to block out the websites of activist news organizations: Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly. In the case of Bulatlat, the country’s longest-running internet news site, they were also subjected to DDoS attacks to render it inaccessible to legitimate site visits.

A probe by Sweden-based Qurium Media Foundation revealed that the attacks came from the Philippine Army, including activities linked to the Chief of Staff for Intelligence of the Philippine Army. This smoking gun evidence gives concrete proof of state forces’ deliberate efforts to take down media outlets that are critical of the Philippine government.

A robust, well-functioning fourth estate is the bedrock of a functioning democratic system. For the government themselves to attack journalists and media outlets is a clear drift into authoritarianism, and must be condemned.

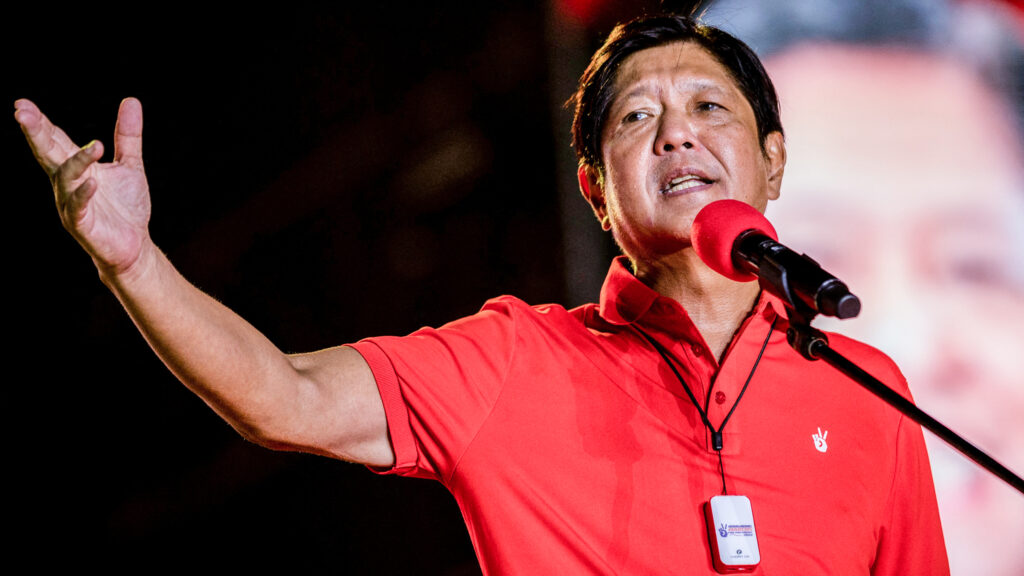

When President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos assumed office in 2022, he made a commitment to protect the lives of journalists and safeguard press freedom in the Philippines. Despite this, attacks on journalists have persisted during his administration.

World Press Freedom Day is a day to recognize the importance of freedom of the press and to raise awareness on the obstacles media practitioners worldwide face, in doing their work. May this day be a reminder to the new Marcos administration to uphold press freedom and protect the lives and welfare of journalists in the Philippines.