Last May, Newshub reporter Michael Morrah exposed the story of 16 Filipino migrant construction workers who were made to sign illegal employment contracts and kept in “prison-like” accommodation to help with the Auckland construction boom. The revelation evoked feelings of outrage from the wider community, but little did we know that the case was merely the tip of the iceberg.

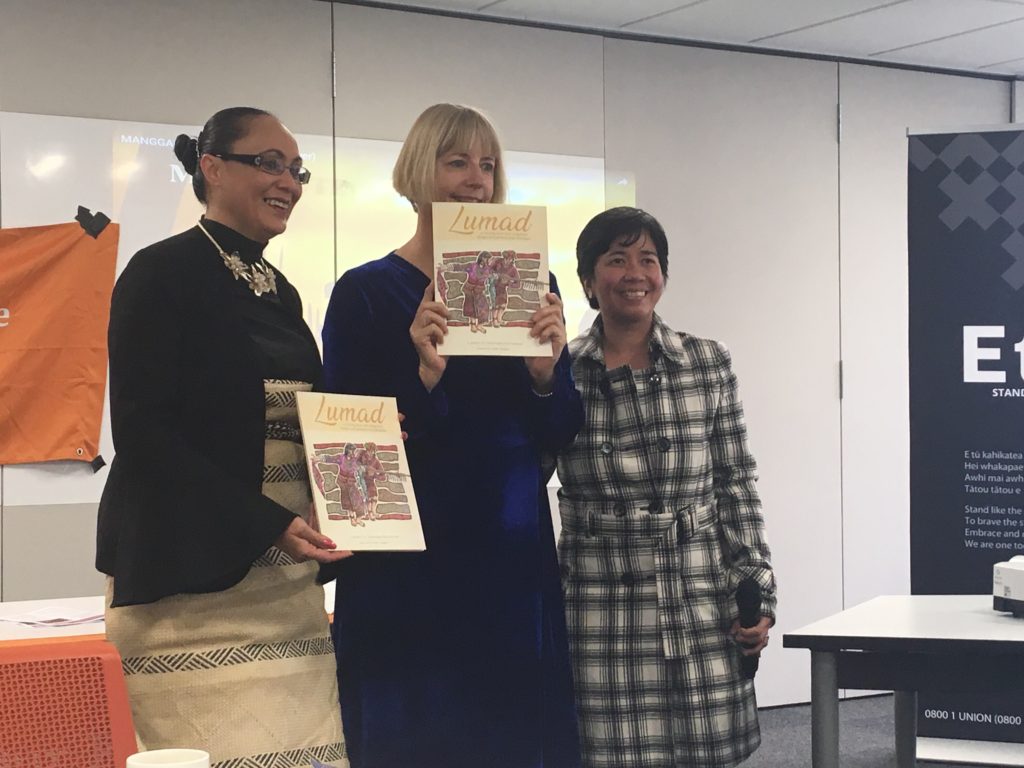

Fast forward three months later and a more comprehensive picture was produced by lawyer Catriona MacLennan, which showed the shocking extent of the exploitation of Filipino migrant workers in the construction industry. In a report for trade union organization, E tū, the problem was shown not merely as a series of isolated cases but part of a normalized culture of deceit that was tantamount to slavery.

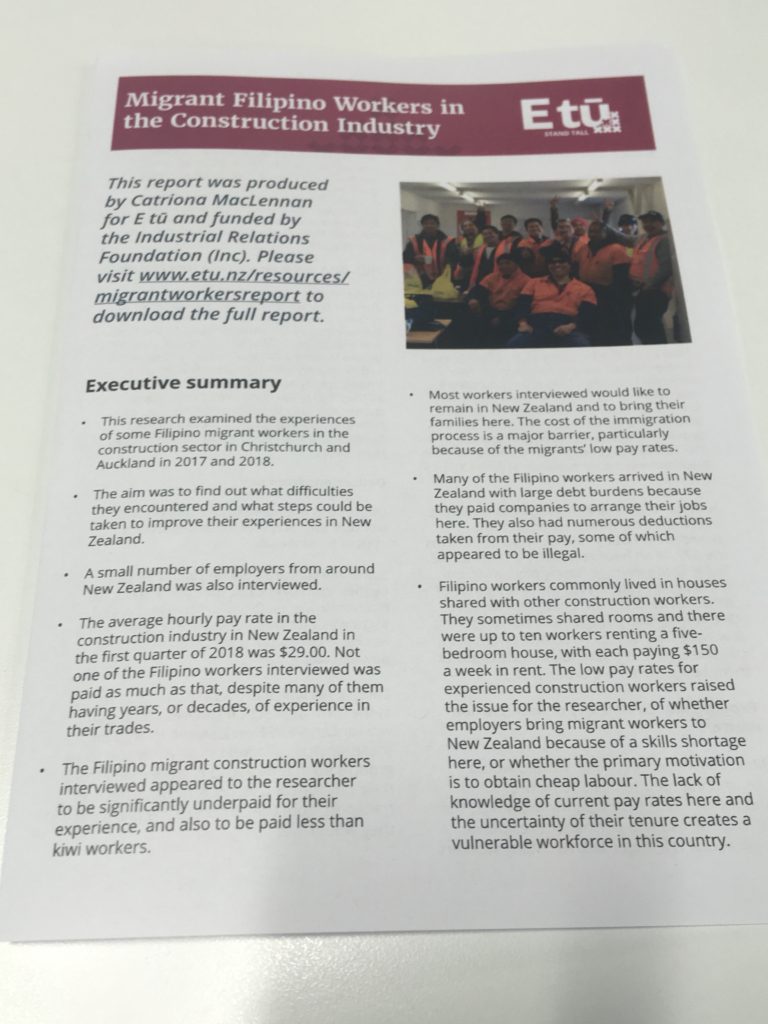

Titled, “Migrant Filipino Workers in the Construction Industry”, the report – which was funded by the New Zealand Industrial Relations Foundation of the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) – showed how Filipino migrant workers were being paid less than their Kiwi counterparts, their wages were being deducted significantly for basic services such as the use of a vehicle to go to work and were also being crammed into overcrowded accommodation which they were billed unfair amounts for.

According to Statistics NZ, the average pay for male construction workers for the first quarter of 2018 was $29.42 per hour. The report, which used 42 different responses from Filipino workers surveyed in both Auckland and Christchurch, did not find a single Filipino construction worker who earned that much. This, despite the fact that many of these workers have years of experience working in the industry in numerous countries aside from the Philippines and New Zealand.

Out of the responses, one worker was paid $28 an hour and a handful were being paid $27 an hour. The vast majority of them were paid a lot less, with some receiving a rate as low as $19 despite being on the job for more than a year. For many of these workers, this poses an even bigger problem since they aspire to permanently reside in New Zealand with their families. However, the minimum salary threshold for the skilled migrant category was pegged at $23.49 per hour as of 2017.

This means that despite their hard work and sacrifice, many of the workers surveyed are not even eligible for permanent residence in the country.

The low pay also complicates other problems these workers have. To find work in New Zealand, they often had to pay labor-hire agencies exuberant fees to do so. The high cost leads them to borrow money from different sources in the Philippines, and they arrive in this country with significant levels of debt already.

These migrants also have to support the financial needs of their families left back home. With low pay, these Filipino workers face a triple jeopardy scenario – having to repay their debts, supporting their families and sustaining their own needs as they live and work in New Zealand.

If their earnings were already squeezed enough, their conundrum is made worse if they availed of dubious “Pastoral Care” services which charge them unjustifiable fees for practical services. These include housing, vehicle use and driver’s license assessment. Sometimes, the visa consulting firms these migrant workers used directed them to the Pastoral Care companies themselves.

The accommodation fee demanded by the Pastoral Care companies were reported to be as high as $150 per week, which housed the client in a four-bedroom house with as many as 20 people sharing the accommodation. Each inhabitant would be placed in a bedroom with three or four other people, despite being told their payment covered the entire room itself.

MacLennan’s findings also reported instances of Pastoral Care companies charging $40 for vehicle use, regardless if the migrant client had used it or not. Respondents also revealed paying $150 for a driving assessment test, despite already having licenses themselves and only needing to have it converted into a New Zealand-approved equivalent.

The scale of the exploitation was appalling, many migrant workers saw their wages deducted as much as $400 a week for three months to cover these miscellaneous and unfair charges. The deductions combined with the remittance they send back home left them with as low as $10 a week to cover their living costs, relying on the goodwill of charity groups to get by.

Several employers were also surveyed as part of the report, and their prevailing view of Filipino migrant workers was that they were “subservient” and “are not used to answering back [to employers]”. This passivity perhaps contributes to their vulnerability.

The high levels of debt most of these workers have, including the burden of having to support a family back home, makes them desperate enough to tolerate exploitation. A support worker interviewed in the report told MacLennan that Filipino workers: “feel that if they complain they may lose their jobs and be kicked out of the country, and they have to return this debt which they have no way of paying.” Their desperation only emboldens exploitative employers to take advantage of them, being aware of their need for an income – regardless of how meager.

The report by MacLennan and of E tu presented several recommendations to the government to take action, including tighter regulations on visa consulting agencies and on Pastoral Care services. A Cabinet minister present presentation of the report, the Hon. Jenny Salesa, informed the attendees that the government already had a proposed action plan to respond to the exploitation which it will unveil in the near future.

What makes the report significant is that it demonstrates the extent of the abuse, it was once thought that migrant exploitation was perpetrated by “a few bad apples”. This report sheds light that the problem has become normalized in New Zealand, how the desperation of migrant workers to support their dependents and to repay their debts makes them willing victims to such injustices.

Therefore, the response the government plans to make should not just tackle the institutional aspect of the problem but also tap into the cultural element of it: making migrant workers aware of their rights, empowering them to demand for these rights and to educate them on the protection New Zealand laws afford them.

What the xxxx these news raised up suddenly on 2018?