Long before New Zealand was exposed to the obnoxious antics of Gareth Morgan and his political vehicle, The Opportunities Party (which is an apt name given its members’ opportunistic tactics), our political landscape already played host to another political party of carpetbaggers.

If Peter Dunne and his United Future political party could adopt a motto, it would have to be the old-age adage: “strike while the iron is hot”. Anonymous for most of its existence, the Party still withstood the test of political time until they finally called it quits earlier this week. With their demise comes the end of Dunne’s 14-year streak of good fortunes, because any review made on the history of United Future will certainly attest to how lucky they have been since 2002.

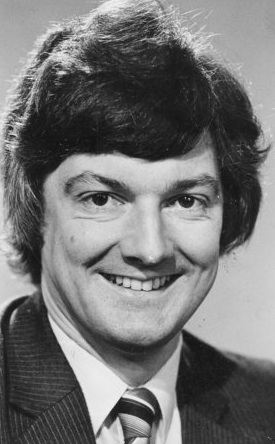

Naturally, the genesis of their story of survival would have to be Dunne’s entry into Parliament in 1984 as the MP for Ohariu under the New Zealand Labour Party. It was considered a safe seat for the National Party, until the charismatic Bob Jones – a well-known businessman – contested the seat thus splitting the right-leaning votes between him and the National Party. This allowed the fresh-faced Peter Dunne, a career bureaucrat, to snag the seat for David Lange’s new-look Labour.

The strain of Labour MPs in 1984 were vastly different compared to the centre-left, progressive batch of the present. It was a Labour Party comprising of Lange, Roger Douglas and Richard Prebble, the latter two are best known for founding the ACT Party – New Zealand’s most neoliberal political party. It can then be deduced that Dunne fell into that same neoliberal school of thought, which he has sugar-coated throughout his career into the more acceptable “centrist” moniker.

He retained the seat the following election, and was rewarded by his Party with the baubles of office: first as an under-secretary in 1987 and later as the Minister for Regional Development and Associate Minister for Justice and the Environment in 1990. The two-term MP had the good fortune of being rewarded with plush government positions despite being relatively unproven.

Dunne’s run of luck did face somewhat of a barrier when his Party lost the 1990 elections to Jim Bolger’s National Party. He was also increasingly at odds with his Party, which has slowly been taken over by left-leaning, pro-unionist individuals who were pushing out the likes of Douglas and Prebble. The peak of this infighting within the Labour Party resulted in the departure of the latter two MPs to form the ACT Party in 1993, also in anticipation of a proposed electoral process reform to be introduced by the 1996 elections.

The advent of the mixed-member proportional system (MMP) gave hope to smaller parties, who found it difficult to break the duopoly on government by Labour and National. In opportunistic fashion, Dunne seized the chance by breaking from the Labour Party in 1994 himself to form Future Party – whose aims were largely undefined other than acting as a political vehicle for the Ohariu MP.

In time for the next election, this new Party was bolstered by other sitting-MPs who had also defected to join Dunne in forming the United Party – a group of centrist MPs coming from both Labour and National. This new enterprise failed to find good fortune in the 1996 elections, with all their members but one losing their seats. The sole survivor was Dunne, who retained his Ohariu seat and eventually became the leader of the United Party. This was largely due to the fact that he was the only surviving MP, staying the same in the 1999 election as well.

It was in 2002 when the United Party made serious headway. First, this minnow party secured the support of Future New Zealand – a Christian values-centric group – which won a respectable 4.33% vote share in 1996. Despite never polling that high, the United Party convinced the former to a merger thus establishing the United Future Party.

Then in 2002, the Ohariu MP had a stellar performance during a televised political debate and made serious media traction as a result. This gave Dunne nationwide recognition which paid dividends during the election that year, netting the Party a remarkable 6.7% in vote share to yield eight MPs. Their success was also buoyed by the disastrous result incurred by the National Party, which lost 12 seats. This breakthrough gave United Future a powerful bargaining position during coalition negotiations, particularly because the ruling Labour Party’s preferred partner – the Alliance – was wiped out from Parliament along with their 10 MPs.

The predicament allowed Dunne to demand concessions from Helen Clark, most notably the establishment of the Families Commission (now Superu) – a research group aimed to produce the best policies to help Kiwi families. While noble, the establishment of a commission is not particularly a “vote winner” due to its abstract nature. It was also appeared as a concession given to the dominant Future New Zealand Party, whose views were Christian-centric. Other policy “wins” that year included the increase in funding support for abuse victims and a promise by Clark’s Labour government that no changes be made to the legality of cannabis – another blatant win for its Christian faction. Despite having a strong position from its election result, Dunne failed to secure any ministerial portfolios for himself or anyone in the Party – it can also be argued that the concessions it won from Labour were not “big wins” either. Still, the Party was played a prominent role in that Parliament with their eight MPs.

However, leading up to the 2005 elections cracks began to show in the caucus. Despite its “united” moniker, the MPs were anything but. The amalgamation of strong, conservative Christian MPs into a Party of centrists was always going to end badly. The most significant sign was a split vote on the Civil Unions Act introduced by the Labour Party, which saw Dunne voting in favour while the rest of his colleagues all voted against. National under Don Brash was also regaining votes lost from the 2002 election, with a hard-line stance against Maori-targeted legislation and an emphasis on conservative values thus swaying voters away from United Future.

The 2005 elections proved brutal for all minor parties, as a two-horse race between Labour and National squeezed votes away from them including United Future. The latter was reduced to three MPs, losing 5 seats. However, United Future’s lucky charm would prove crucial again as their support would be sought after by Helen Clark since her Party fell short of a majority.

Dunne with all his luck was made Minister of Revenue, outside of Cabinet and won several policy concessions as well. Again, none of these policies could be worthily categorized as “wins” with the most prominent being the adjustment of income tax brackets and extra funding for more police officers. The latter policy would be severely overshadowed by a policy concession secured by the other Party which gave its confidence-and-supply to Labour that year, New Zealand First, which secured funding for an additional thousand front-line police officers.

United Future would suffer a further blows during the 2005-2008 Parliament when one of its MPs, Gordon Copeland, resigned due to disagreements with the caucus (despite being a paltry 3 MPs). The infighting between the moderates and the fundamentalist Christians in the Party became even clearer, since the reason for Copeland’s departure was largely because of conflicting views on social issues such as Sue Bradford’s anti-smacking bill. The Outdoor Recreation Party, a political group which had backed United Future before the 2005 election also pulled the plug on their alliance. These events were testaments to the Party’s opportunism coming back to bite, they merged with other parties hoping to boost their chances without properly taking into account the potential compatibility of the different factions.

This series of blunders would prove costly to Peter Dunne’s political party, plummeting even further in the 2008 elections registering just 0.87% of the party vote share. He would remain the party’s sole MP until its eventual demise this year, though not without any rewards. Despite its role propping up the Labour Party for nine years, United Future were still invited to the table by the new National government of John Key. The two entered a confidence-and-supply agreement which would span all three terms of the National-led government’s reign. Their arrangement also allowed Dunne to safely secure the Ohariu seat, which National did not seriously contest for the next nine years to prevent vote-splitting from losing Dunne his seat. This was similar to the deal National made with ACT in Epsom.

The Key government retained Dunne as Minister for Revenue, while also bestowing him as the Associate Minister for Health, Conservation and the Minister responsible for the GCSB – the government’s intelligence service. The latter role would land him in murky waters, when classified intelligence reports were somehow leaked to political journalist Andrea Vance. The fiasco prompted Dunne to relinquish his responsibilities to the GCSB, but as luck would have it he was not forced out of favour from the National-led government and carried on with his other portfolios.

Dunne’s fortunes would only allow his survival, rather than a revival of his career nor his Party’s. United Future never regained the traction that would see them steer past the same level of support as in 2002, its only lifeline was their leader’s hold of the Ohariu seat – and even that was courtesy of another Party’s (National) goodwill rather than Dunne’s own merit. But even the seemingly perpetual marriage between the latter and his electorate would prove to have its limits, in early 2017 an election survey found that Dunne was lagging behind his rival in the electorate – Labour’s Greg O’Connor – by double digits. Within weeks, United Future’s leader announced his retirement from politics thus casting serious doubts about the future of the Party.

He would still retain his seat of Ohariu and his ministerial portfolios until the 2017 elections, which he did not intend to contest. The Party appointed its president, Damian Light – a thirty-something politico and multiple election candidate – as its new Party Leader. The move made very little difference to the fortunes of United Future, with an unknown personality taking the helm. During a live television debate on TVNZ, Light hoped his ascension into the throne left vacant by Dunne would reinvigorate support for the Party given his youth and focus on “future generations”. Regardless of what clever marketing strategy he would employ, the Party was still doomed given that their only security in the past 12 years was Dunne’s electorate seat. Without the security of a seat, the Party would have to secure 5% of the party vote under MMP rules – an insurmountable task given United Future had not even broke the 1% mark in the last three election cycles.

Thus it came as no surprise when on election night 2017, the Party registered a mere 0.1% of the party vote share and were booted out of parliament. Luck had finally ran out for the Party that benefited from shrewd political mergers and opportunism.

Most would be hard-pressed to cite United Future’s biggest political achievement, it is evident that their most remarkable attainment was their political survival from the 2005 elections onward. They had no properly defined identity from the start, claiming to be a Party of centrists which serves no purpose given that the broad-church nature of both Labour and National made those parties the de facto home for centrist voters.

Yet, as luck would have it, Peter Dunne and his United Future project defied the odds and found some shred of relevance each time during the past fifteen years. They hold the distinction of having the longest continuous role in government in the last 100 years, though that is a feat easily achieved when one has no inherent principles and would be willing to abide by the ethos of the government of the day to secure their place in power.