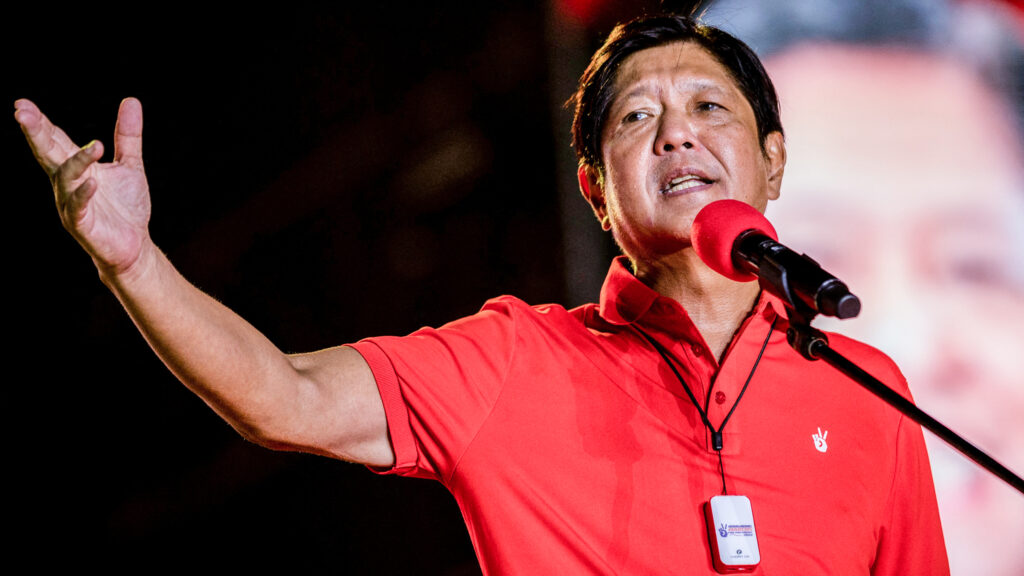

Amid widespread backlash, the bill creating the controversial Maharlika Wealth Fund (MWF) has passed Senate scrutiny, putting President Bongbong Marcos’ centerpiece economic policy on course to becoming a reality.

Intended as a sovereign wealth fund, the MWF proposal attracted criticism for its plan to use retirement savings and funds from the state-owned health insurance company as seed money. Although this provision would be removed in a later revision of the bill.

Objections were also raised when Marcos moved to certify the bill as “urgent” – thereby expediting its passage in Congress – despite the lack of any emergency that would necessitate its immediate passage. Even the President’s own allies questioned the wisdom of rushing a bill that involves enormous amounts of public funds.

Despite being unpopular, proponents touted the MWF as a “a vehicle for economic progress“. Benjamin Diokno, Marcos’ finance secretary, even announced that the MWF will deliver “greater socioeconomic impact”. President Marcos himself defended the MWF’s flaws, saying it was Congress’ job to “make the bill perfect”.

However, it’s more than fair to say establishing the MWF is poorly-timed and unnecessary. Sovereign wealth funds typically use the surplus funds of the country for its seed money, but the Philippines posted a a budget deficit of US$1.95 billion in February. Total outstanding national debt also reached Php13.86 trillion in March, which begs one to ask if a sovereign fund is a prudent use of limited public funds at a time of great debt.

Beyond economics the country also suffers from a deficit of public goods, with school infrastructure being a prime example. At the start of Marcos’ term an audit revealed that the Philippines has a shortage of around 40,000 classrooms. The Education Department also cited that the Philippines would need to spend at least Php100 billion a year to resolve the shortage by 2030.

The teachers needed to teach in classrooms is evidently a key need, but as it stands our public schools are suffering from chronic staffing shortages. Yearly pay increase for public school teachers has outstripped the rate of inflation, but only marginally, which doesn’t make the profession that much enticing leaving these staffing shortages to persist.

The Philippines also receives more than its fair share of natural calamities, often incurring large financial and human costs. The unrest at the Mayon volcano is perhaps the most recent example, with thousands already displaced from their communities. A more profound eruption will (God forbid) also imperil copious amounts of public infrastructure, and cause locals to lose their livelihood.

Funding the resettlement of victims of natural calamities is a more sensible way to invest in the Filipino than the MWF. Focusing our limited public funds on the social good, or to control the budget deficit and the national debt, would be much better ways to invest in the Filipino people than an unnecessary sovereign wealth fund.

But Marcos’ desire to create a legacy project shrouds his ability to think rationally. Funding for public schools, teachers’ pay increases, or fast-tracking human resettlement after a natural disaster would never be certified urgent under this government – despite being actual emergencies.

With the bill establishing the MWF only needing the President’s signature, it is definitely a done deal. One can only hope now that the eventual fate of Marcos’ wealth fund won’t become a bigger tragedy than the natural calamities that hit the country, itself.