When Rodrigo Duterte campaigned during the 2016 presidential elections, he vowed to kill “as many as 100,000 people” in his crackdown on illegal drugs. Many dismissed that as mere campaign hyperbole, disqualifying the possibility that the then-mayor of Davao City would actually push through on his “promise”.

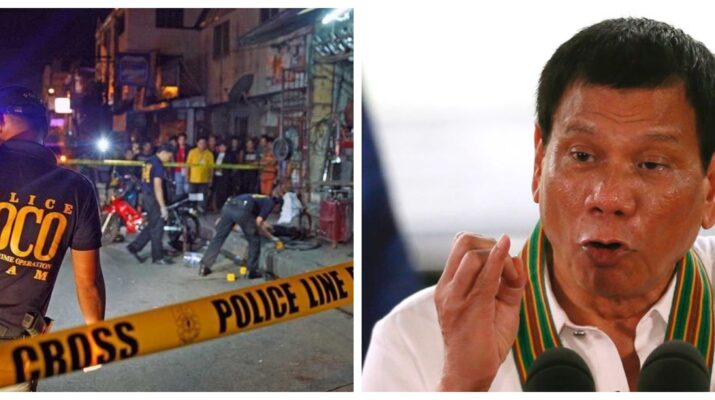

Having finished his term in office already, it is certain that the Duterte presidency will go down in history – even beyond Philippine history – as one of the bloodiest. Figures from the Philippine National Police (PNP) reported in 2019 that 3,062 killings were treated as “deaths under inquiry” involving illegal drugs; however, no less than the United Nations’ Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) have said that the police figures are underreported.

The UN’s pronouncements are not baseless, after all another government agency – the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) – cited a much higher figure, at 6,215 deaths. Human rights groups, on the other hand, believe that number to be much higher with their estimates between 12,000-30,000 fatalities.

Even more concerning, and further proof of the Duterte regime’s brutality, the Administration’s 2017 end-of-year report included 16,355 “homicides under investigation” as an “accomplishment” – part of its drug war campaign. The deceased were not high-profile targets who were confirmed drug peddlers, rather they were fatalities still under inquiry – it is a certainty that several of them would be innocent.

The killing of innocent Filipinos – without due process, most of them not even seeing a single day in court – was a key feature of Duterte’s so-called “drug war”. Even worse, this homicidal campaign was perpetrated by the country’s own police force.

The Duterte regime repeatedly dismissed accusations of human rights abuses, insisting that the police only killed in self-defense against drugs suspects who attempted to “fight back”. This despite a wide-reaching probe on the drug war in 2021 found at least 52 cases where the victim allegedly fought back were proven to be false.

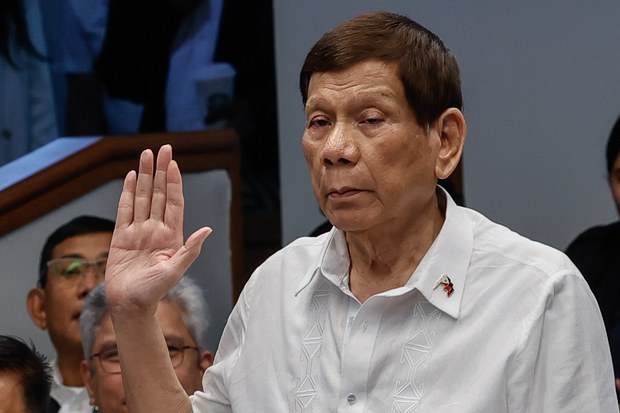

Yet whether or not human rights abuses did occur under the former administration was still a matter to be debated; that is, until 28 October when Rodrigo Duterte himself fronted an inquiry into his so-called “drug war”. Appearing before the Senate’s Blue Ribbon Committee, the former president confirmed how he instructed the PNP to conduct drugs-related operations himself.

Duterte declared that he ordered Philippine police to “encourage” suspects to fight back so that cops can have an excuse to kill them. Under oath, he told the Senate in Tagalog: “What I said is this, let’s be frank, I said encourage the criminal to fight, encourage them to draw their guns. That was my instruction, encourage them to fight, and if they fight, then kill them so my problem in my city is done.”

The former president even confirmed the existence of the infamous death squads that first gained notoriety in Davao City when Duterte was its mayor. The latter told senators during the hearing that he had a group of “gangsters” he would instruct to “kill” persons to crack down on crime in the city.

Duterte bared that this death squad model was replicated on the national level when he assumed the presidency in 2016. More telling, the former chief executive said that – as president – the PNP chiefs who served under him also became death squad commanders.

Parallel to the Senate investigation, the House of Representatives (HoR) also has an ongoing inquiry into the drug war where police officials during Duterte’s regime had appeared in. One of those police leaders, retired Colonel Royina Garma, testified that there was even a “rewards system” to encourage cops to kill drug war suspects.

The existence of a rewards system for cops who kill their targets have been echoed by at least two other sources as well: first, by former senator Leila de Lima who – as former chair of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) – investigated the death squads in Davao City under Duterte. And second by Arturo Lascañas, a retired police officer who claims to be an ex-gunman for the Davao death squad but became a whistleblower in 2017.

Although Duterte denies the existence of a rewards system, it cannot be refuted that high-level police officers during his term were rewarded with plum positions in government. His police chief in Davao City, Bato dela Rosa, was immediately promoted as police chief of the entire nation; a one-star general, the Duterte ally leapfrogged his upperclassmen to the top position which became very controversial at the time.

Upon retiring from the force, Dela Rosa was also made director-general of the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) in 2018 and became senator the year after. Garma herself was installed as head of the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO), despite still being active in the PNP at the time of her appointment.

Another police official who had been linked to the Davao Death Squad, Isidro Lapeña, was appointed commissioner of the Bureau of Customs (BOC) in 2018. During his term he was embroiled in a massive Php11 billion shabu (crystal meth) smuggling case that eventually pressured the Duterte government to replace him in 2018.

Despite his term as Customs head ending in disgrace, Lapeña was still given a cushy job as director-general of the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) shortly thereafter. The whistleblower Lascañas said that Lapeña was the “brainchild” of the DDS’ abduction operations, which may explain his favorable treatment by the Duterte government despite having no skills relevant to the positions he was appointed to.

The same can be said about Catalino Cuy, who was made undersecretary of the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) in 2016, before being appointed chairman of the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB). Questions were raised when these high-ranking police officials were being given plum government posts after serving the post, but their appointments make sense now in light of the revelations about the drug war.

Individually, the testimonies of whistleblowers like Lascañas and former PNP chief Jovie Espenido, the confession of insiders like Garma, or the incriminating statements made by former president Duterte himself during the Senate hearing, may not be enough to implicate the latter on charges of crimes against humanity for the drug war.

But what does dispel any doubts as to whether human rights abuses occurred in the bloody campaign is the fact that the statements Duterte made at the Senate inquiry corroborate accounts given by the whistleblowers and the insiders like Garma. Given the consistency of the facts heard, there should be no questions now that the Duterte regime did, in fact, commit grave crimes against humanity during its war on drugs.

The facts that have been made public can no longer be questioned as mere inventions designed to produce a political outcome. These are facts that all point to the conclusion that there was a systemic abuse of human rights that was sanctioned by the state.

With the facts becoming clearer, one can only hope that Duterte and his cohorts’ day at the International Criminal Court (ICC) draws nearer for they will surely face justice when it comes.

#InvestigateDuterte is TheDefiant.net’s campaign to bring former President Rodrigo Duterte and his cohorts to justice for the crimes against humanity they committed while in government. You can read more stories in this series by clicking here.