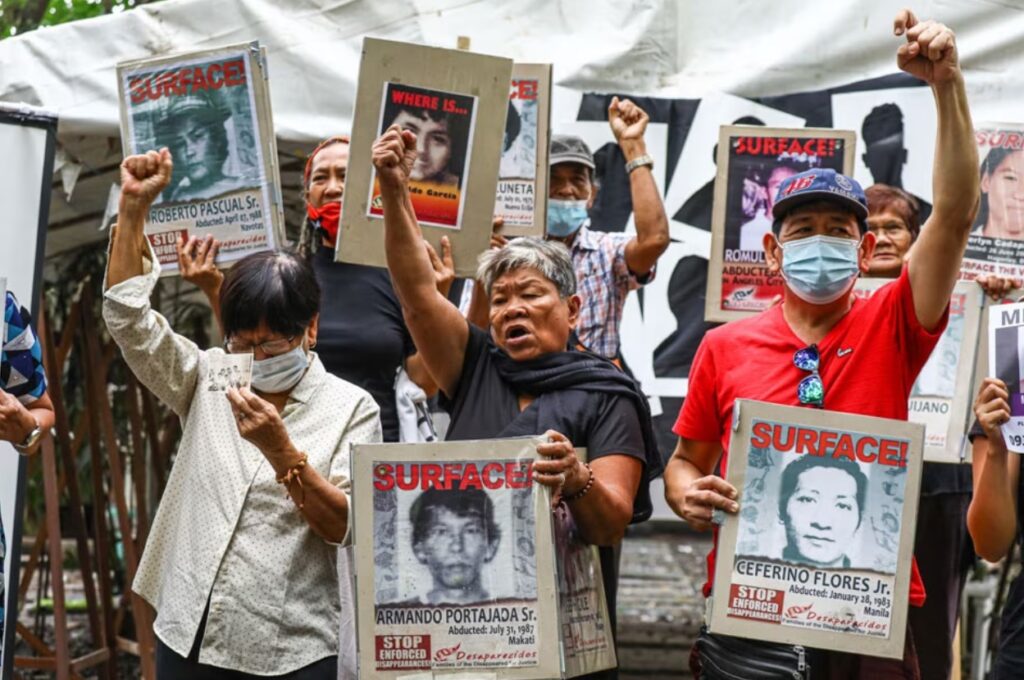

Enforced disappearances were a common occurrence under the first Marcos regime. By the time Ferdinand Marcos Sr. was ousted from power in 1986, there were 926 activists, trade unionists, and other political dissidents who went missing.

Most of these cases were never resolved and the disappeared persons were never seen again. These people are what we now refer to as desaparecidos, the Spanish word for “disappeared”, and are another testament to the brutality of the first Marcos regime.

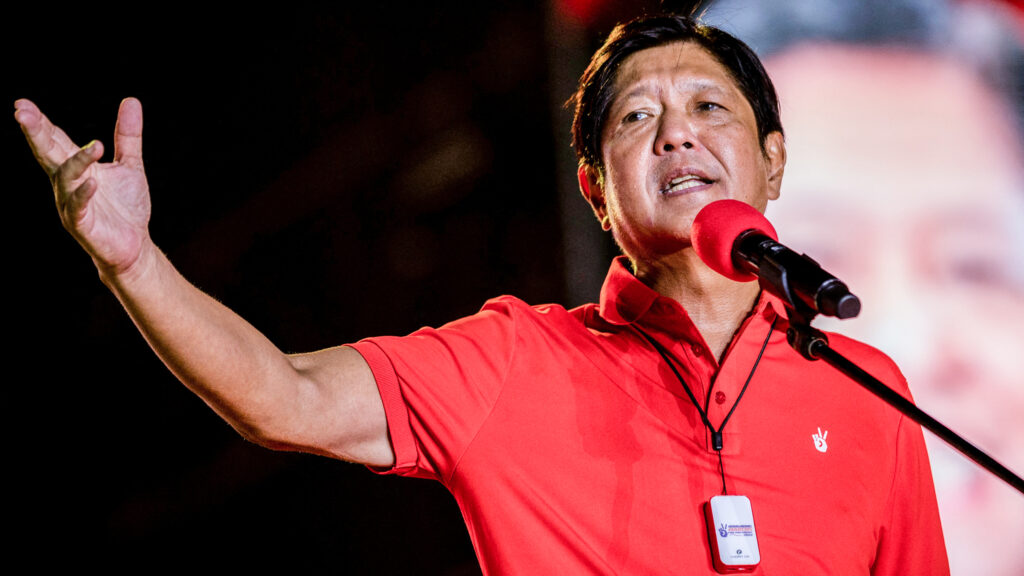

The lack of closure would already be painful to the surviving families of these desaparacedios, but even worse is seeing the late dictator’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., ascend to the presidency as well. Not only are the victims’ families still waiting for justice against those responsible, now they see the political clan that tormented their disappeared loved ones return to power as well.

Bongbong Marcos’ rise to power is problematic not only because he restores Marcos family rule in the Philippines, but more so because he has denied that any abuses even happened during his father’s rule to begin with. What is most chilling, however, is that the enforced disappearance of activists is once again happening under this new Marcos regime.

Last April, two human rights activists went missing in Rizal province after undergoing a medical check-up. Gene Roz Jamil “Bazoo” de Jesus and Dexter Capuyan were reported missing by their families after losing contact with them on the night of April 28. Both were student activists at the University of the Philippines – Baguio campus and continued their activist streak beyond university life.

De Jesus was working as an information and networking officer for the Philippine Task Force for Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, while Capuyan was an activist-leader based in Benguet province. The Cordillera Human Rights Alliance (CHRA) suspect that the two are now in government custody, as the police and military have both accused Capuyan of being a combatant with the New People’s Army (NPA).

Capuyan was tagged as an alleged officer of the communist rebel group by the Department of National Defense (DND) offering a Php1.8 million bounty for his capture. The Cordillera activist was also among 649 persons included in a “terrorist watchlist” released by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2018, which the department embarrassingly trimmed down to just eight names due to lack of evidence.

The Government had wrongfully accused Capuyan of being a communist rebel before, it wouldn’t be a surprise if his recent abduction is connected to the authorities’ suspicion of him being an enemy of the state. But if they admitted before that they had no evidence implicating the activist in the underground rebellion, what evidence do they have against him now?

State forces also need to show evidence why they are keeping Bazoo de Jesus in custody too, given he has no history of being suspected as a communist rebel and the only fact that would pique the Government’s interest is his activism.

Less than a month after De Jesus and Capuyan went missing, two more student-activists also met the same fate. Patricia Cierva and peasants’ organizer Cedric Casaño were also abducted in Cagayan province on May 18. In their case, eyewitnesses were able to pinpoint soldiers from the Philippine Army’s 501st Infantry Brigade as the culprits.

Cierva was a prolific student-activist in UP Manila, before taking a job with the Kabataan Partylist after graduating. Casaño meanwhile, was a staunch environmental activist who has campaigned against open-pit mining at the Didipio gold and copper mine in Cagayan Valley.

Much like Bazoo de Jesus and Dexter Capuyan, these two young activists have no tangible links to the NPA and are clearly being targeted for their staunch activism and opposition to the Marcos regime. They are thought to be the 22nd and 23rd victims of abduction since the start of Bongbong Marcos’ presidency last 30 June.

Several activists have already gone missing before the four mentioned. Peasants’ organizer Maria Elena Pampoza and women’s rights activist Elgene Mungcal went missing in Tarlac province on 3 July. Mary Joyce Lizada and Arnulfo Aumentado, two indigenous’ rights activists, also went missing in April in the province of Oriental Mindoro – four days before De Jesus and Capuyan’s abduction.

There were also other activists who were abducted, but eventually resurfaced by the police and military. Stephen Tauli, another indigenous’ rights activist, was abducted by police and military units on August 21 but was located by a search party 24-hours later.

Armand Dayoha and his fiancée Dyan Gumanao, both development workers based in Cebu province, were abducted by unidentified men – suspected to be state forces – in January and experienced psychological torture, being forced to admit that they were NPA cadres. The couple had no involvement in the communist rebellion and only became persons of interest by the state due to their human rights activism.

Therein lies the reason why the likes of De Jesus and Capuyan, Cierva and Casaño, and the other individuals mentioned are in the cross-hairs of the police and military: they are actively seeking social justice and act as a check on the abuses of power by the Government.

This new wave of desaparecidos under President Bongbong Marcos is reminiscent to what history saw during the first Marcos regime: this is a systemic campaign to silence dissent and intimidate other activists from obstructing the Government’s agenda.

Pushing back against this new wave of Marcos desaparecidos, including demanding for the resurfacing and release of abducted activists, is crucial to ensure history does not repeat itself and we won’t see over 900 activists go missing again. To relent against this campaign of enforced disappearances is to assert that activism is not a crime, and it should not be equated to terrorism.