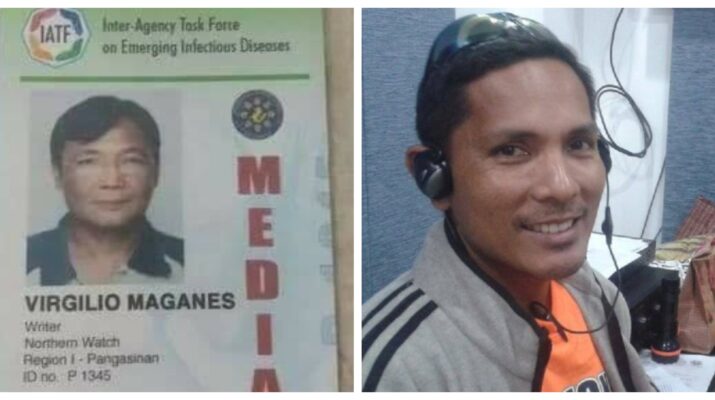

Gunmen onboard a motorcycle shot dead radio commentator Virgilio Maganes in Pangasinan yesterday, as he was about to enter his house.

As a member of the progressive journalists’ organisation, the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP), Maganes was no stranger to threats on his life. In November 2016, he narrowly survived an attempt on his life as motorcycle-riding gunmen opened fire on him as he was riding a tricycle.

The veteran journalist only survived by playing dead after being hit with a non-fatal gunshot wound. As he lay motionless, his would-be assassins left a sign near him which read: “Drug pusher, huwag pamarisan” (English: [He’s a] Drug pusher, don’t emulate him!).

It can be recalled that President Rodrigo Duterte’s infamous “war on drugs” was at its peak during that time. The gunmen were obviously trying to smear Maganes and disguise his assassination as part of the campaign to crack down on illegal drugs.

Unfortunately, Maganes was not as fortunate in the second attempt on his life, making him the 18th media practitioner to be assassinated under the Duterte regime.

[Alert] NUJP member who survived 2016 slay try shot dead

A journalist who survived a slay attempt in 2016 was shot dead…

Posted by National Union of Journalists of the Philippines on Monday, November 9, 2020

He is also the third journalist to be killed this year, following the killing of radio reporter Jobert “Polpog” Bercasio in September. Much like Maganes, the former was also killed by riding-in-tandem assailants and died on the spot.

Bercasio was a staunch commentator on ecological issues in his home province of Sorsogon. He was particularly interested in illegal logging activities and mining operations happening in the province, a blight on its natural environment.

It is obvious that the radio commentator’s campaign against these powerful industries cost him his life.

Bercasio’s death followed the killing of another radio personality, Dumaguete radio reporter Cornelio “Rex” Pepino last May. He was on board a motorcycle with his wife when they were shot at by gunmen riding another motorcycle, killing the journalist instantly.

Pepino’s death came only two days after World Press Freedom Day, a sad indictment of the media environment in the Philippines – often cited as one of the most dangerous countries on Earth to be a journalist.

In fact, in Dumaguete alone, two other radio broadcasters were killed before Pepino.

Edmund Sestoso was shot dead by motorcycle-riding gunmen on 30 April 2018 on his way home from work. He was also a member of the NUJP and hosted an afternoon radio program where he would comment on pressing social issues in Dumaguete.

A year later, Sestoso’s colleague in radio broadcasting – Dindo Generoso – would also be killed by assassins on board a motorcycle. The radio announcer was shot dead on his way to the station to host his regular radio program.

The three Dumaguete radio broadcasters, Virgilio Maganes, and Jobert Bercasio all share a common trait among them – they engage in hard-hitting journalism that criticises powerful entities.

There are now 18 media practitioners who have been assassinated under the Duterte regime. This killing spree is what has made the Philippines the 5th most dangerous country in the world for journalists in 2019, according to the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

In 2018, the Centre for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) also declared the country to be the most dangerous in Asia for members of the fourth estate.

This climate of hostility towards journalists is a result of President Duterte’s constant demonisation of the media.

Less than a month after he was elected as president, Duterte remarked that journalists were “not exempted from assassination” if they were a “son of a bitch”.

He has also taken aim at established media outlets who dared to openly criticise his government. The President hit back and blasted these news organisations one by one.

President Duterte repeatedly admonished the Philippine Daily Inquirer (PDI) in 2016, even accusing its hierarchy of tax evasion, which forced its owners – then the Prieto family – to sell the outfit to a company owned by billionaire tycoon Ramon Ang, a close ally of the President.

Duterte has also taken aim at online news site Rappler.com, particularly its founder and editor, Maria Ressa. Using the same script from his attack on PDI, the President again accused Ressa of skipping on her news organisation’s owed taxes – a claim vehemently denied by the latter.

More famously, the Duterte administration ensured that ABS-CBN – once the country’s largest broadcaster – would be taken off the air. Singing from the same songsheet, the President again used the same tax evasion accusation to win public support against the media giant.

President Duterte constantly peddles the lie that these media organisations are either violating the law, are controlled by foreign interests, or even that they’re being used by the CIA to topple the Philippine government.

By demonising media outlets and practitioners, President Duterte has created a hostile environment in the Philippines for the fourth estate. It has led to journalists being constantly targeted by violence or by unfounded legal challenges.

This kind of behaviour by the Philippine government has caused the country to be among the world’s most dangerous for journalists.

However, this tactic is very effective for the Duterte government to tighten its control over the country.

By tarnishing the media, to a point where killing journalists has become so normalised, it can silence dissent or intimidate those journalists into giving his administration positive publicity.

In exchange, however, the country will cease to be a free society.