With the stroke of President Duterte’s pen, the province of Palawan has been split into three new entities pending a plebiscite in 2020.

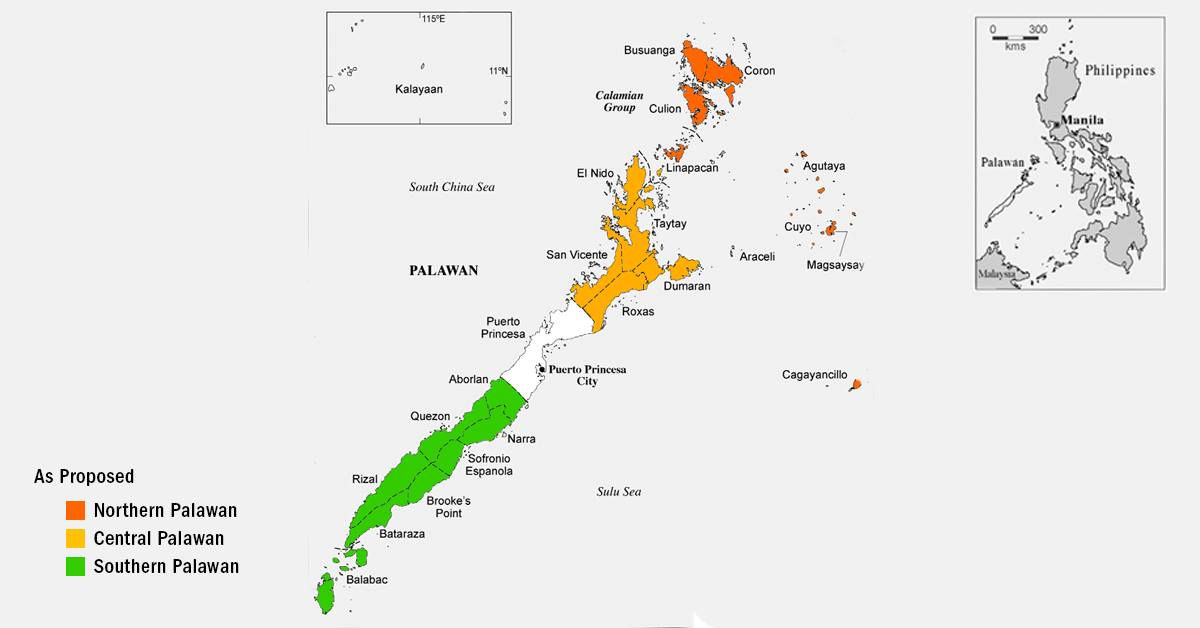

Republic Act No. 11259 divides the slender landmass into the new provinces of Palawan del Norte, Palawan Oriental, and Palawan del Sur – with the latter as the mother province. The current seat of local government, the city of Puerto Princesa, will become a “highly urbanized city” (HUC) independent of any of the three provinces.

However, the final say will come from Palawan’s residents who will vote on a plebiscite come 2020 deciding if the provincial split will happen or not. Nonetheless, this move by Congress, with the approval of the President, raises many concerns not just among the locals but at a nationwide setting also.

Palawan is the country’s westernmost frontier, it faces the West Philippine Sea – the disputed maritime territory where the Philippines is at risk of losing the islands it claims to the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Anders Corr, a Europe-based foreign policy analyst, previously stated that the division of the province into three smaller ones will make it more vulnerable to external threats. He said that having three separate provincial governments, rather than one unified body, will give China more opportunities to gain a foothold in the mineral-rich island.

Senator Risa Hontiveros also expressed a similar sentiment: “If China has aggressively and arrogantly exerted its claim on the West Philippine Sea, it can now easily conquer the three provinces which are now reduced as small local government units.”

Aside from having geopolitical significance, there are valuable mineral resources in the province which has been the subject of intense disputes over the years. Mining in the province in particular, has spurred contentious debates, with many firms extracting nickel, chromite and copper ore in Palawan for years.

Many local government officials are resolute in opposing mining in their province, but some have also allowed it in the past. This destructive economic activity has been blamed for Palawan’s environmental woes, including soil erosion, chemical spills, acid waste drainage and the toxicity of water in the area.

There have been repeated moves to outlaw mining in Palawan entirely, but a combination of lax government oversight as well as suspected corruption in the bureaucracy have allowed many mining firms to continue their detrimental operations on the island. (EXAMPLE 1, EXAMPLE 2)

With a diluted provincial government, it would be easier for exploitative mining companies to pillage Palawan’s natural resources. The three proposed provinces will also be starved for revenue, and can use the decrease in income to allow the mining firms to operate more openly in their jurisdiction.

Local organizations have been vocal in opposing the plan also, their chief complaint is that the gerrymandering was being pushed through hastily – with little public consultation. As the 2020 referendum will only include voters affected by the three new provinces, it will exclude residents of Puerto Princesa – which will stand as an independent, HUC upon approval.

An advocacy group, Save Palawan Movement (SPM), have started a petition opposing the break-up and explain their rejection by saying: “Dividing Palawan means dividing a key biodiversity area like Victoria Anepahan Mountain Range (VAMR) into two provinces. The proposed bill failed to take into account the various natural resource laws and policies that affect Palawan”.

In short, the division of the province into three will make environmental oversight much more difficult – thus, making Palawan’s pristine natural setting at risk to destruction.

The plan to break Palawan reeks of bad news, it is a concern for foreign policy, for the environment as well as a flippant disregard of the democratic process. It is a measure that is filled with so many adverse consequences that one can be forgiven for thinking that the author of the measure, Palawan representative David Francis Ponce de Leon, perhaps had ill intentions when drafting the bill.

Senator Sonny Angara, a proponent of the bill in the upper chamber, defended the move by saying it was logical to do so given Palawan is the largest province in the Philippines in terms of land area. But while that may be true, the population of the province at present remains among the lowest in the country.

As of June 2018, Palawan had a total population of less than 1 million. At the 2015 Census, there were 27 provinces with at least one million residents each – none of them are being proposed for gerrymandering.

Politicians receive their mandate from being representatives of the people, if there are already enough representatives in proportion to the local constituency – what is the rationale for adding more officials?

There are simply too many reasons why the breaking-up of Palawan is a bad idea, but unfortunately it seems that very few elected officials are conducive to these concerns. The people will ultimately decide the fate of this plan come 2020, and hopefully they will act more rationally than the politicians they elected to represent them.