As announced before the start of the 2018 FIFA World Cup last Friday, the 2026 edition of the prestigious sporting event will be hosted by a trio of hosts comprised of the United States, Canada and Mexico. This was announced by FIFA President Gianni Infantino after the “United 2026” bid was declared successful, beating Morocco’s own challenge to host the event.

Already the projected benefits for all three countries for their successful bid is massive: they expect an estimated US$14 billion in revenues for hosting the event, including a net benefit of US3-4 billion for the North American region. There is also a US$5 billion in short-term economic activity for the continent from hosting the World Cup, and will create 40,000 jobs and US$1 billion in incremental worker earnings across North America. (Source: https://www.ussoccer.com/stories/2018/02/08/18/37/20180208-news-united-bid-2026-world-cup-could-create-5-billion-in-economic-activity-north-america)

The titillating figure would surely be envied by Morocco, who had ambitions for hosting the event themselves and pledged to invest US$16 billion in infrastructure if their bid was successful. It would have been an enormous capital expenditure for the developing north African nation but one they were willing to make, given the figures a host nation stands to gain from the FIFA World Cup.

Given how lucrative hosting the most popular sporting event in the world can be, it begs to be asked if New Zealand and Australia should look to host a future iteration of the World Cup themselves.

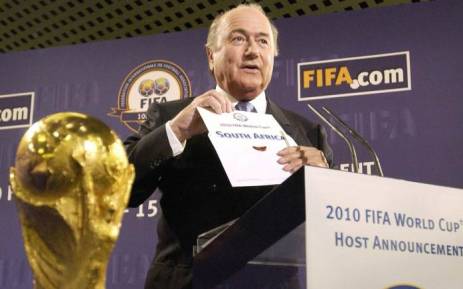

After all, the continent of Oceania is the final continent on the planet not to have hosted the FIFA World Cup – sans Antarctica of course. Africa can boast having the honour of being World Cup hosts after South Africa received the 2010 edition.

The closest that Oceania, or the Asia-Pacific region even, came to hosting the World Cup was when Australia submitted a lone bid for the 2022 edition – which Qatar eventually won. Recent revelations by former FIFA head Sepp Blatter said that their bid “never stood a chance”, given that the world football body believed “they would not earn much” if the event were to be held “Down Under”.

However, it might be a different story if Australia teams up with their trans-Tasman neighbors New Zealand for a “United” bid of their own. A large part of the “United 2026” bid was because of its unifying message, at a time when the global political climate is getting feistier.

As US Soccer president Carlos Cordeiro declared after being announced the victor: “Football is the only victor. We are all united in football.”

As part of a potential bid, Australia and New Zealand – while taking the lead roles – could also incorporate their Pacific neighbors. It would be a momentous occasion not just for the Pacific island-nations but for FIFA and global football as well, if the event were to be hosted down under – it will finally make the FIFA World Cup a truly global affair.

It is also worth noting that from the 2026 World Cup onwards, the football tournament will be expanding to 48 teams from the current 32-team competition. This essentially guarantees New Zealand a World Cup berth already, and given that the successful World Cup host will be given an automatic spot in the tournament there could be room to accommodate a team from the Pacific – with Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and the Solomon Islands all having the chance to see their respective flags raised on an ultra-popular global festivity.

Australia, while being geographically located in Oceania, is officially part of the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) which they are currently the champions of having won the AFC Cup in 2015. A World Cup place would be very easy for them to achieve, and thus would not have much care for an automatic berth anyway.

What Australia would be interested in, as with New Zealand, is the chance to host the FIFA World Cup on their own soil and reap the economic benefits it yields. For their failed 2026 bid, a total of AU$48 million of taxpayer money was committed just for the bid itself – undoubtedly, Australia taxpayers would like to see a return on that investment at least sometime in the future.

In New Zealand’s case, the prospect of becoming co-hosts of the FIFA World Cup should be a no-brainer given how beneficial hosting the 2011 Rugby World Cup had been for the country. A 2012 report by then-Sports Minister Murray McCully showed that hosting that event added NZ$573 million to the economy and created 7,840 part-time and full-time jobs.

A tourism perspective report by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) also showed that a total of 133,200 visitors came to New Zealand for the Rugby World Cup itself, and those tourists were estimated to have spent an average of NZ$3,400 each or a total of NZ$387 million. All those benefits were achieved with an NZ$300 million expenditure, and take note that New Zealand were the solitary hosts of the event hence the costs were placed solely on us.

Whereas a united bid with Australia will share the costs of hosting the FIFA World Cup, and given that the latter is the larger economy it would be inevitable that they will take the lion’s share of the host cities chosen – which means that the Australians will also have to pay the larger portion of the bill.

While that would also mean that since New Zealand are allocated fewer host cities, the sheer scale of the World Cup’s popularity – which by then will be hosting a much greater number of countries than the current editions – will mean that the benefits will even out anyway and would still be a lucrative opportunity for Aotearoa New Zealand.

The FIFA World Cup dwarfs the Rugby World Cup in viewership and global focus, it is expected that the net benefit we stand to gain from hosting the global football tournament will also outweigh the gains we felt from the 2011 Rugby World Cup.

It is also worth mentioning that for the United 2026 World Cup, the Final will be held at the MetLife Arena in New Jersey – which the naming rights are held by the MetLife Insurance Corporation. The prospect of hosting the ultimate game of the tournament means that those naming rights just increased in valuation, giving the insurance firm great exposure.

Similarly, other corporate-named stadiums slated to become venues for 2026 World Cup games include the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, Georgia, the AT&T Stadium in Dallas, Texas and the Bank of Montreal Field (BMO Field) in Toronto, Canada. All these corporations stand to gain from brand exposure from the World Cup, which means that hosting the event can also become beneficial for the private sector.

As such, Australia and New Zealand can also tap partnerships with their respective private companies for help in shouldering the expenses for a potential World Cup bid. Perhaps New Zealand can tap Westpac for help, and in turn have games at the Westpac Stadium? Or perhaps existing stadiums such as Mt. Smart ,which is publicly owned, can sell their naming rights to a private corporation and the revenue could help in shouldering expected costs of hosting the FIFA World Cup.

There are many ways to finance the bid for the event, either way the FIFA World Cup is a gigantic global event which poses worthwhile benefits for New Zealand and Australia. It should be noted that the earliest edition that both countries can host is in 2034, given that the 2022 event is already hosted by an AFC-member country which bars another member of the confederation (Australia) from hosting the next two events.

If a bid for 2034 would become successful, New Zealand has 16 years to prepare which is ample time to construct the needed infrastructure and amenities to make us successful hosts for the World Cup. Overall, the prospect of becoming a future host for one of the world’s most popular sporting and cultural events is entirely feasible and evidently lucrative for our country and Australia also.