Striking a balance between sound economic policy and environmental responsibility can be a conundrum for state governments. Adding indigenous rights to that equation confounds the issue even further.

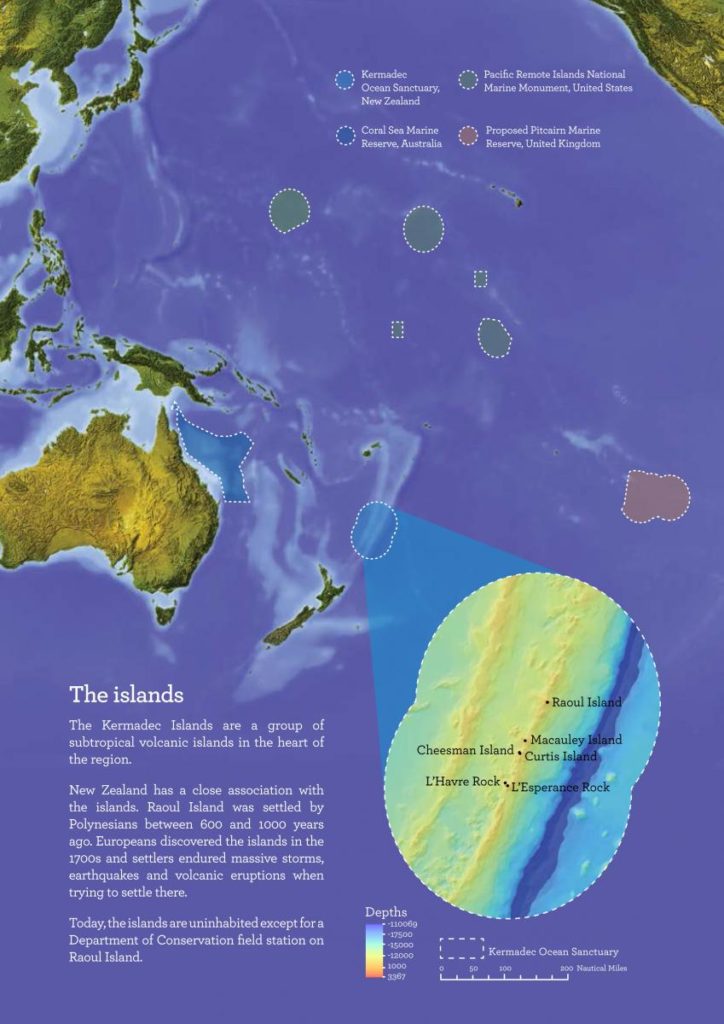

This is the problem faced with the proposed Kermadecs Ocean Sanctuary which the former Prime Minister Sir John Key announced in 2015. The ambitious project aims to declare the 620,000 sq. km. Kermadec Islands zone as a protected area, thereby banning all fishing and mining activities in the vicinity.

The proposal was cheered by environmentalists, citing the importance of preserving the marine life in the area – which happens to also be among the most biodiverse in the world. The protected area is home to different species of dolphins, whales and endangered sea turtles, while also being part of the pathway for millions of migratory birds each year.

However, it is also an important revenue-stream for New Zealand fishing entities particularly for Maori. Last year, a total of twenty tonnes of fish were hauled from this area alone representing a substantial resource for those involved. If the Kermadecs would be closed off from any fishing activity, access to such resource would be gone including for tangata whenua.

When Key announced his intention for the Kermadecs, he did not consult with all stakeholders particularly with Maori Iwis. The announcement was made in front of the United Nations in New York, which makes one speculate if the former Prime Minister’s intentions were drawing on narcissism and aimed at receiving global praise rather than an informed decision taking into account the needs of the people he represented.

Under the Treaty of Waitangi, the Crown “confirms and guarantees to the Chiefs, tribes and individual Maori full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their fisheries”. Maori customary fishing is a right protected under New Zealand law, this means that the Crown (the government) cannot infringe Maori fishing access to fishing grounds their ancestors had operated in for centuries – this includes the Kermadecs.

A concession could have been possible between the Key government and Maori Iwis, but unfortunately a consultation with the latter was not even attempted. Te Ohu Kaimoana, the Maori entity tasked with overseeing their fishing rights under the Treaty, planned to take the government to court over their premature declaration of an ocean sanctuary and its consequential ban on their fishing activities.

This deadlock was avoidable, had the Key government made the necessary consultations with all stakeholders. However, it was obvious that the former prioritized winning kudos from their international counterparts as opposed to fulfilling Treaty obligations. An elder from the Maori tribe, Ngai Tahu, revealed that Maori would have been open to a compromise had they been consulted.

In the aftermath of the Labour-NZ First coalition agreement, it was widely speculated that the planned Kermadecs Ocean Sanctuary would be scrapped with the mainstream media attributing it to NZ First MPs’ close ties with fishing corporations. That theory is very short-sighted given that fishing companies are not the only ones affected by the ban on fishing, but more importantly are indigenous New Zealanders who are protecting their customary fishing rights and source of livelihood.

Protecting the Kermadecs from a blanket ban on all fishing activity is vital for the welfare of rural Maori and for the fishing industry which is a big part of New Zealand’s economy. It has to be protected from the callousness and arrogance from both National and the Greens.