Political prisoner: a person imprisoned for their political beliefs, and/or participation in non-violent political activity. The motivation for detaining a political prisoner is purely political, most likely for opposing the government of the day.

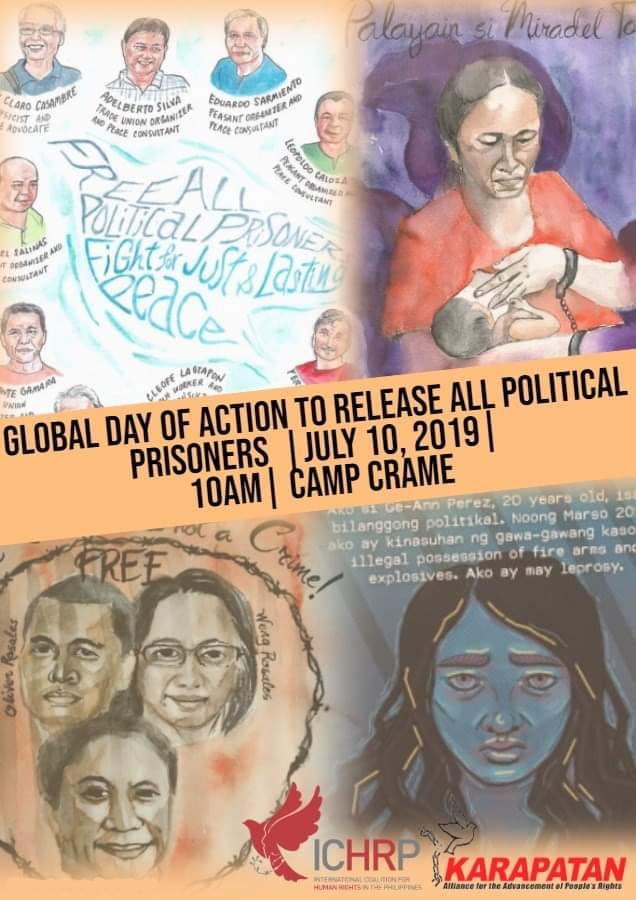

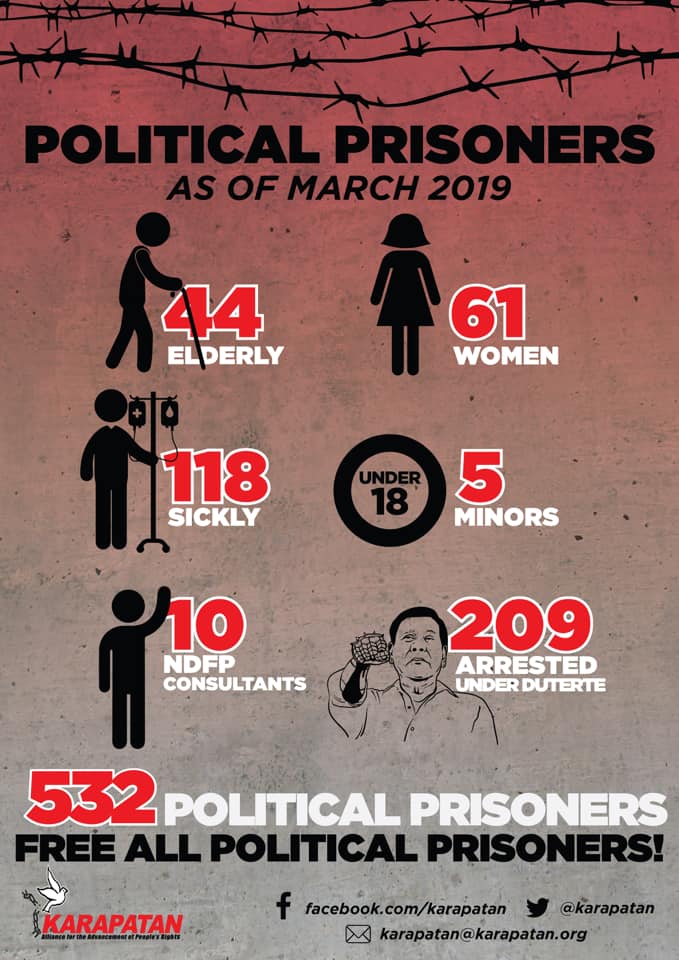

Human-rights group Karapatan and the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP) have both estimated the number of political prisoners in the country to be at 532, nearly half of this number – 209 individuals – were arrested during the three years under President Rodrigo Duterte alone.

Many of whom are mothers who have just given birth, senior citizens who are suffering from illnesses, and consultants who were negotiating a peace deal with the government. Despite the non-violent nature of their endeavors, they have been charged with serious offences such as murder, arson, or crimes related to terrorism.

One example is Miradel Torres, an activist with the women’s rights organization Gabriela. She was arrested in late 2014, when she was already four months pregnant, and nearly suffered a miscarriage due to the harsh nature of Philippine prisons and the ill-treatment afforded by jail guards.

In her fifth month of incarceration, Torres gave birth to a baby boy at a hospital, but was immediately returned to her jail cell where she had her prescribed medication confiscated. She faces charges of frustrated murder, and for allegedly being a combatant of the revolutionary New People’s Army (NPA), but how could she possibly fight a guerrilla war if she was an expectant mother?

Take the example of Maoj Maga, an organizer with the trade union Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU). He was in the middle of a casual basketball game with friends near his home in San Mateo, Rizal when a group of armed men approached him, blindfolded him, and forcibly pushed him into their vehicle.

Maga was detained on charges of illegal possession of firearms, and for committing murder in the province of Agusan del Norte, thousands of miles away and a location the union organizer has never visited in his life. Despite the implausibility of these allegations, he was convicted for those “crimes” and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Accusing activists of illegally possessing firearms is nothing new, two middle-aged women were arrested by police precisely on those charges. Gabriela leader Corazon Javier and Azucena Garubat of peasants’ group NAMAPA were both arrested after police allegedly “found” firearms – including two hand grenades and a grenade launcher – in their respective homes.

Both were arrested on the same morning as the deadly police operations in Negros Oriental which left 14 people dead, two of the deceased were brothers of Garubat. Meanwhile, Javier was first coerced to affix her signature on a search warrant and after which the policemen found two hand grenades and a cache of firearms inside the elderly woman’s home.

It also begs to ask how two middle-aged housewives could fight a battle against well-equipped, well-trained police commandos, and as the photo of their arrest shows both were not dressed for combat either. What Javier and Garubat both have in common, however, is that they are both activists who protest the policies and actions of the government.

Being critics of the government is what unites both women detainees with Miradel Torres and Maoj Maga, which makes one question the veracity of the charges filed against them. While rebellion is indeed punishable by law, dissent is a democratic right and being critical of the government does not make one a rebel combatant.

But how can we know for certain the Duterte administration is merely conducting a witch-hunt on activists, and that these political prisoners are truly innocent? Past examples have shown that state authorities conduct operations that go beyond the rule of law.

Last month, journalist Margarita Valle was wrongfully apprehended by policemen and detained for 11 hours after being mistaken for a communist rebel who is wanted for charges of arson and murder. The veteran writer suffered an asthma attack while in custody, and reported that the men who abducted her did not show her any arrest warrant or explain to her why she was being held in custody.

Valle’s erroneous arrest shows that the police are not beyond error, that they can accuse even a sickly, elderly lady of violent crimes such as murder and arson simply based on a hunch. It also shows that the intelligence gathering of state security forces is prone to error, even national police chief Oscar Albayalde admitted that his agency “lacks [the] capability to verify intelligence info“.

That revelation makes one wonder how many of the political prisoners they currently have in custody are truly guilty of the crimes they are accused of?

It is also worth mentioning that Valle is a writer that is openly critical of the Duterte administration, is it a coincidence that she, too, has been accused of being a rebel combatant who dubiously committed serious crimes? Had it not been for the immediate protests of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), maybe the wrongfully-accused journalist would have been on the same boat as the 523 political prisoners in the country.

Hence, this 10th of July – a day earmarked to call for the release of all political prisoners in the Philippines – may we realise that not everyone accused by the government of committing crimes is truly guilty. Being an activist does not make one a terrorist, organizing a union does not amount to sedition, being a vocal critic of the government does not make one a rebel fighter.

Spare a thought for the political prisoners, for their “crime” may only be exercising their democratic rights.