In the latest line of decisions made by the Coalition Government that has sent the liberal opposition into hysteria, Oceans and Fisheries Minister Shane Jones announced that work on the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary has been halted.

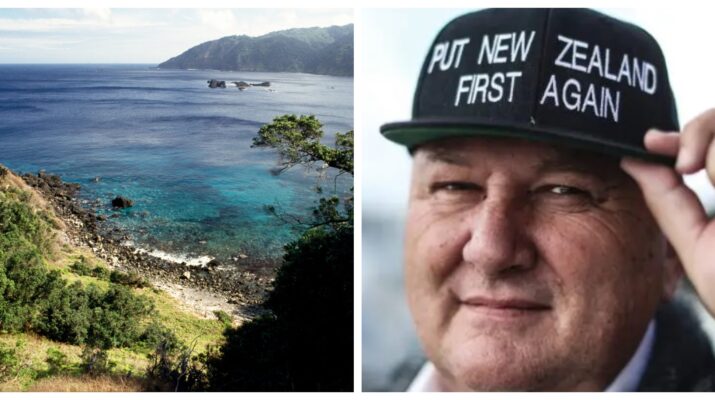

Announced by former Prime Minister John Key in 2015, the proposal was to create an ocean sanctuary in the Kermadec Islands spanning 620,000 square kilometers and would have been the largest in the world.

The area represented by the proposed Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary is 15 percent of New Zealand’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). By declaring the entire marine space as a sanctuary, economic activities would be heavily restricted in it – particularly fishing.

While the Kermadec Islands contain rich amounts of natural resources, it is also home to a wealth of biodiversity and a pristine natural environment that is equally valuable to New Zealand’s identity.

Rare species of sharks and endangered dolphins inhabit the area, in addition to humpback whales migrating south traversing within the Kermadec Island chain. It is also a popular destination for birdwatchers, with many of the Kermadec’s islets are home to important bird colonies.

There is no question that this biodiversity needs to be protected, but even without the ocean sanctuary making it over the line there are already adequate measures in place to protect the pristine natural environment of the Kermadecs.

A marine reserve spanning 745,000 hectares protecting the Kermadecs has been in place since 1990. This protection stretches 12 nautical miles from the shores of its islets and has allowed the marine life of the area to thrive.

The scrapped Ocean Sanctuary would have extended the protected area to 200 nautical miles of its coasts. Given that the present protections have already given rise to a flourishing flora and fauna, such an excessive increase of the restrictions is unnecessarily detrimental to New Zealand’s economic activities.

Despite first being proposed in 2015, the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary has failed to come to fruition because of issues that remain unresolved to this day. When the idea was first announced eight years ago, Māori iwi had voiced their concerns as the sanctuary would have restricted economic activity for them as well.

Māori tribes had been given fishing quotas in the Kermadecs as part of a 1992 Treaty settlement, and the Ocean Sanctuary would have deprived them of that right. This was also a large barrier why the Ocean Sanctuary did not push through under the previous Labour-majority Government.

Not only would New Zealand’s important fishing industry be impacted by the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary proposal, but Māori would also be denied one of their major settlement wins and lose access to their customary fishing grounds.

The superfluous enlargement of the Kermadec Islands’ protected zone would have been a classic example of New Zealand shooting itself on the foot. With the economy already confirmed to be in a recession last week, restricting economic opportunities further would have been insane.

Such an unnecessary expansion of the protected marine area posed very dubious benefits for New Zealanders. However, it is a decision that many prominent foreigners celebrated when it was first announced in 2015.

Billionaire film producer James Cameron lobbied for an extension of the protections for years, and it was well-documented how then-US State Secretary John Kerry had influenced the former Key government to establish the ocean sanctuary.

It became very obvious that the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary was promoted to appease prominent international celebrities, to the disadvantage of Kiwi industry and indigenous groups. Oceans Minister Shane Jones, deputy leader of the nationalist New Zealand First party, would have always found the idea incongruous to his own views and that of his party.

With the Coalition Government having already signaled their desire for an export-led economy, the Kermadec Ocean Sanctuary had been dead in the water since this new administration was installed. But beyond that, the decision to halt the ocean sanctuary was a signal that New Zealand interests would be put before globalist perceptions once again.