A project as ambitious as the Duterte administration’s “Build-Build-Build” infrastructure plan could not have gone through without becoming entangled in controversy, and it looks to have reached its first major hurdle as the funding details of one of its projects has come under scrutiny.

The Chico River Pump Irrigation project is the first large-scale infrastructure project to be financed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) under President Duterte so far. It aims to irrigate 8,700 hectares of land in the provinces of Kalinga and Cagayan, providing a stable and ample supply of water for agricultural use, thus helping thousands of farmers.

The CRPIP comes with a price tag of Php4.3 billion, with Php3.6 billion to be loaned from the state-owned China Export-Import Bank as an Official development assistance (ODA). This is the source of much of the controversy, that the loan agreement signed between the Philippines and the PRC is “onerous” or unusually highly-advantageous to the latter.

(READ: PREFERENTIAL CREDIT BUYER’S CREDIT LOAN AGREEMENT between Philippines-China)

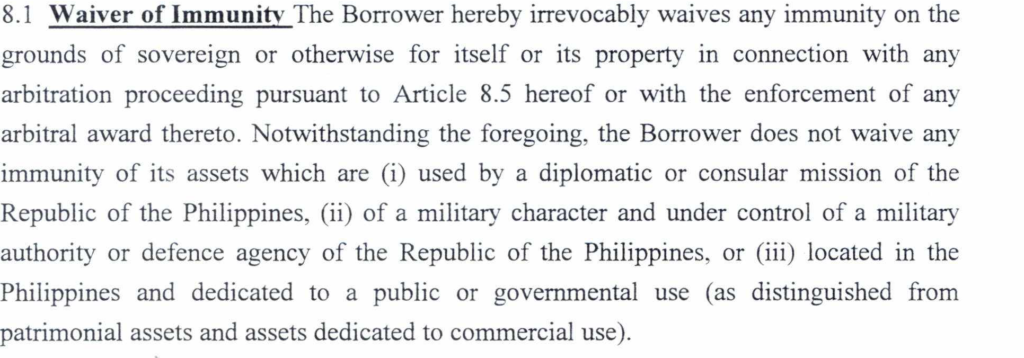

At first glance, nothing seems amiss about the loan: the full amount is US$62 million, with an interest rate of 2% p.a. and a maturity period of 20 years, including a 7-year grace period. The debate is spurred by Article 8.1 in the loan agreement, referred to as the “Waiver of Immunity” which reads:

The clause states that the Philippines (“the Borrower”) waives its sovereign immunity on its “patrimonial assets” and also “assets dedicated to commercial use”, should it be enforced in an arbitration award. This means that in the event of a default or a dispute in the loan agreement that will be subjected to an arbitration process, these “patrimonial assets” could be expended to satisfy “the Lender” – the PRC.

To make matters more complicated, Article 8.4 of the loan agreement mandates that any arbitration process should be conducted in Beijing, under Chinese laws. Even though the project is situated in the Philippines, the loan will be paid for by the Philippines and the pump irrigation will affect only Filipinos, the PRC will have the final say in the arbitration process – should one be needed.

More interestingly, Article 8.8 – or the “Confidentiality” clause – mandates “the Borrower” to keep all terms, conditions, and the standard of fees of the loan agreement secret. This means that the Philippine Government is required not to disclose the fine details of the deal to any party, not even to its own Filipino people – who are ultimately the ones who will pay back the loan.

These caveats are what prompted lawyer and former congressman Neri Colmenares to speak out against the Chico River Pump Irrigation Project, calling the terms of the CRPIP’s loan agreement “onerous” or “one-sided” in China’s favour. He also condemned the Duterte Government for pitting the Philippines’ natural resources as a “collateral” in this transaction with the PRC, a country that has long had desire to dominate the West Philippine Sea.

In a Facebook post (see below), Colmenares argued that several articles of the loan agreement were “unconstitutional” and should therefore be dismissed as null and void by the Supreme Court. The Bayan Muna party-list chairman likened the provision regarding “patrimonial assets” as tantamount to using Philippine sovereign rights and natural resources as a loan collateral, but this was disputed by the Department of Finance (DOF) who insist there is no collateral in the said loan.

Finance chief Carlos Dominguez declared as early as May 2018 that our loans from China do not entail any collateral, in response to fears that the Philippines could face a “debt trap” as have Sri Lanka. Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo, on the other hand, contradicted him by saying that the system of using natural resources as collateral is “a standard in such contracts”.

This same fear was allayed by Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio who said that in the event of a default, China could seize oil & gas resources in Recto Bank (also known as Reed Bank) in the West Philippine Sea. This is because of Article 8.1 which waives the sovereign immunity of the Philippines’ over its “patrimonial assets”.

Given the PRC and the Philippines’ long-running territorial dispute in the area, for the Duterte Government to agree to such a clause that could undermine our claims on these assets is a slap in the face.

Spokesperson Panelo made a massive gaffe in the process by stating that Carpio is wrong in his analysis because “patrimonial assets” have to be declared as such by law, and that there was no law designating Recto Bank as one. Carpio immediately disproved that statement by pointing out that a 1972 law did declare Recto Bank as a patrimonial asset.

Admitting his mistake, Panelo then shifted his defense of his Government’s loan agreements by insisting that the Philippines “would never default” on its US$62 million loan. While it is true that the size of our external debt relative to our GDP is at a healthy level, this does not make it acceptable that natural resources were put at stake to a hegemonic power which has a desire over our country’s territory.

The spokesperson also defended the seemingly one-sided loan agreement, likening it to an ordinary bank which dictates the loan conditions on potential debtors. “When you [take a] loan from the bank, it’s always the terms of the bank,” Panelo argued.

While that may be true, a rational consumer would walk away from loans that have conditions which are blatantly unfavourable or unfair to them. They do so in order to protect their best interests, which tells us either that the Duterte Government is not acting in the best interests of our nation, or that they acted irrationally.

Rational consumers who seek financing would decline unfair lenders and instead find another lender with more favourable loan conditions. In the Philippines’ situation, there are other lenders who offer better loan terms than China – a salient example is Japan, our largest source of ODA loans which pegs its interest rate at 0.1% p.a. as it did when with the Manila Subway project.

So why wasn’t Japan tapped for the CRPIP also? According to the Philippines’ chief economist Ernesto Pernia, the Government chose to borrow money from China in order to win “more friends”.

Pernia says though that Japan cannot shoulder all of the Philippines’ development needs, so China is still an important partner to have on our side. “More friends is still better than fewer friends.” | @ClaireJiao

— CNN Philippines (@cnnphilippines) February 21, 2018

This tells us that the loan agreement signed with the PRC is not only to fund the CRPIP, but also to win China’s favour and to gain “new friends”. While the Duterte Government may believe they are applying a form of “diplomacy” in doing so, they seem to be oblivious to the Asian giant’s track record for “debt trap diplomacy” and risk falling victim to such phenomenon themselves.

What is even more perilous however, is that if the Government slips up in their plans, it is the Filipino people who suffer in the end.

2 thoughts on “Understanding the problematic Chico River Pump Irrigation project”

Comments are closed.