As Filipinos cheer on the Philippine delegation during the 30th Southeast Asian Games, they have also rallied behind an unlikely neighboring country during the competition — Timor-Leste. The youngest nation in the Asian continent had difficulties chasing its first medal in the biennial sporting event, and the hosts Philippines threw in their support to the Timorese not to go home empty-handed.

There are many reasons why Filipinos would be fond of Timor-Leste.

For one, their two countries share a similar colonial background – having both been occupied by Iberian states, Spain and Portugal respectively. The two countries are also the only nations in Asia that are predominantly Roman Catholic.

But the ties that bind Timor-Leste and the Philippines should be their similar experiences in fighting for national liberation. Just as the latter fought to free themselves from Spanish rule, only for an opportunistic United States to swoop in immediately after they left, Timor-Leste also fought valiantly against Portuguese rule only to be denied self-determination by their neighbour Indonesia.

Until 1975, the country was a colony of Portugal and was named “Portuguese Timor“. The western half of the island Timor was part of the Dutch East Indies and would later join Indonesia when the latter received independence from the Netherlands in 1949.

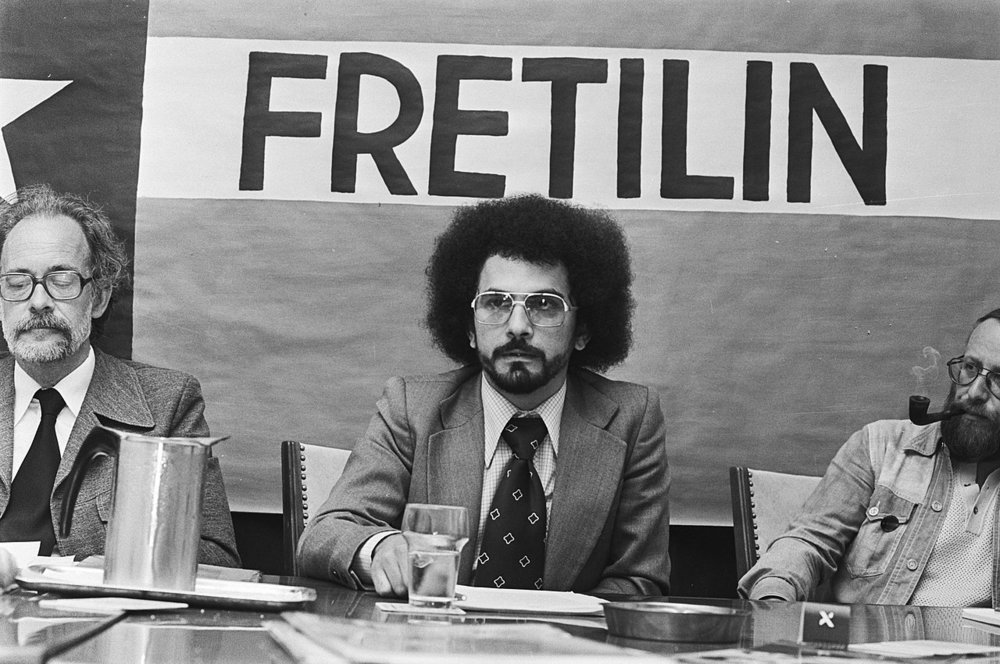

It was in 1974 when the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin) formed as a national liberation organisation, waging a war against the Portuguese until the colonizers eventually left in November the following year. However, Fretilin’s work would not cease just yet as less than a month after the departure of the Portuguese, Indonesia would invade the country.

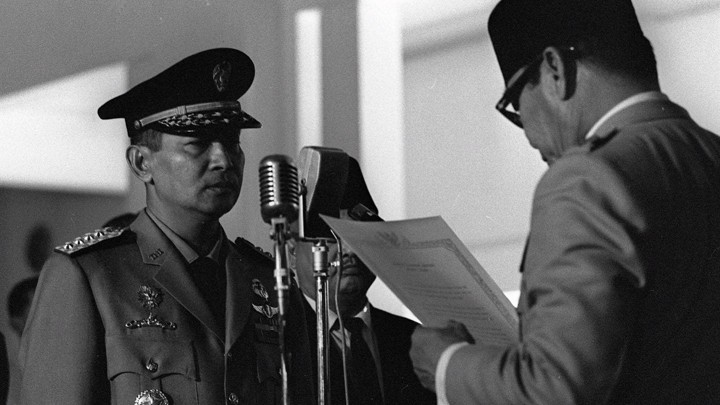

Under Operation Lotus, the Suharto-led Indonesia would begin a brutal occupation of East Timor. The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconcialition in East Timor stated that there were over 102,000 conflict-related deaths in the country from the beginning of the occupation in 1975-1999.

Missile gunboats and OV-10 Bronco bombers were used profusely to decimate the Timorese guerrillas. Western intelligence gathering allowed the Indonesian troops to track down and neutralise key Fretilin leaders such as their elected leader Nicolau dos Reis Lobato (who was killed in 1978) and later his successor, Mau Lear (captured and executed in 1979).

This led to a new generation of Fretilin leaders, ones who espoused a nationalistic message, to rise up and reinvigorate the Timorese struggle.

The Fretilin members who survived the initial Indonesian onslaught regrouped and elected Xanana Gusmao as their new leader. A young Timorese intellectual living in exile in Portuguese West Africa (now Mozambique), Jose Ramos-Horta, was also selected as their de facto Foreign Minister and tasked with disseminating the message of their struggle to the international community.

Ramos-Horta’s work in the international sphere would be instrumental in helping his home country gain solidarity overseas. He was appointed as the Permanent Representative of Fretilin to the UN for a decade, speaking on the suffering of the Timorese under Indonesian occupation before the UN General Assembly.

It was Gusmao’s message of Timorese nationalism and Ramos-Horta’s solidarity work abroad that reinvigorated their struggle. But it was another phenomenon entirely which ultimately dealt the final blow to Indonesia’s bloody occupation – the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

Unrest in Indonesia caused by worsening economic conditions led to the dictator Suharto’s resignation in 1998, and was succeeded by a more moderate BJ Habibe as president. The latter voiced his openness for an autonomous East Timor, and called for a referendum on the fate of the country in 1999.

Despite covert ops work by the Indonesian government (with support from the U.S.) to set-up anti-secessionist militias in East Timor that harassed to vote against independence, the 1999 referendum overwhelmingly delivered a pro-independence result. But the newly-elected Indonesian President Habibe would not allow the Timorese to break free so easily.

The events proceeding the referendum verdict would now be remembered as the “East Timorese Crisis”, when Indonesian-backed militias swarmed Timorese communities with violence in retaliation for seceding. During this period an estimated 1,000 Timorese – mostly civilians – would perish, with millions of dollars of damage to infrastructure and property as well.

Joseph Nevins’ book, “A Not-So-Distant Horror: Mass Violence in East Timor“, quoted Ramos-Horta as saying that Indonesia “wanted to wreak havoc before leaving East Timor” (p.84). Geoffrey Robinson’s report on the Crisis said that Indonesia’s response was part of a cultural pattern of “running amok” (p. 275).

While Indonesia troops withdrew from East Timor when the United Nations entered in 1999, pro-Indonesia militias would continue to ravage the Timorese until 2002. That year, the newly-elected Timorese President Xanana Gusmao formally declared independence – christening the former Portuguese colony as the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste.

The long and bloody struggle of the Timorese people draws plenty of similarities with the Philippine anti-imperialist struggle. For centuries both nations were under the rule of an Iberian power, and given sham independence only to be usurped by a new imperialist power – Indonesia and the U.S. respectively.

Armed struggle domestically was vital, but so too was the work of winning solidarity overseas. In some ways Ramos-Horta is Timor-Leste’s answer to the Philippines’ Jose Rizal – winning the hearts and minds of the global community.

When it seemed like the two countries were on the verge of breaking free from their second colonial masters, they faced utter decimation by an aggressive force – the Japanese invasion for the Philippines, and the onslaught of the pro-Indonesia militias for Timor-Leste.

While Filipino sports fans cheer jubilantly for Timor-Leste in the 30th SEA Games, we should also continuously rally behind our Southeast Asian neighbour in other affairs too. Closer ties should be built among our two countries, drawing on our shared experience with colonialism and our common heritage as predominantly-Catholic nations.