Philippine history has enshrined the 21st of September as the date when deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. However, another date that we Filipinos should familiarize ourselves with in understanding that dark era of our country’s story is the 26th of January — the start of a period of mass dissent remembered as the First Quarter Storm (FQS).

During the first three months of 1970 (hence, first quarter), beginning on the 26th of January, thousands of demonstrators – led by student activists – voiced out their frustrations with the Marcos regime. Students, blue-collar workers, and other members of mass organizations staged a string of rallies calling out the worsening economic conditions of the country and their government’s fealty to the United States — which at this time, was engaged in a major conflict in neighbouring Vietnam.

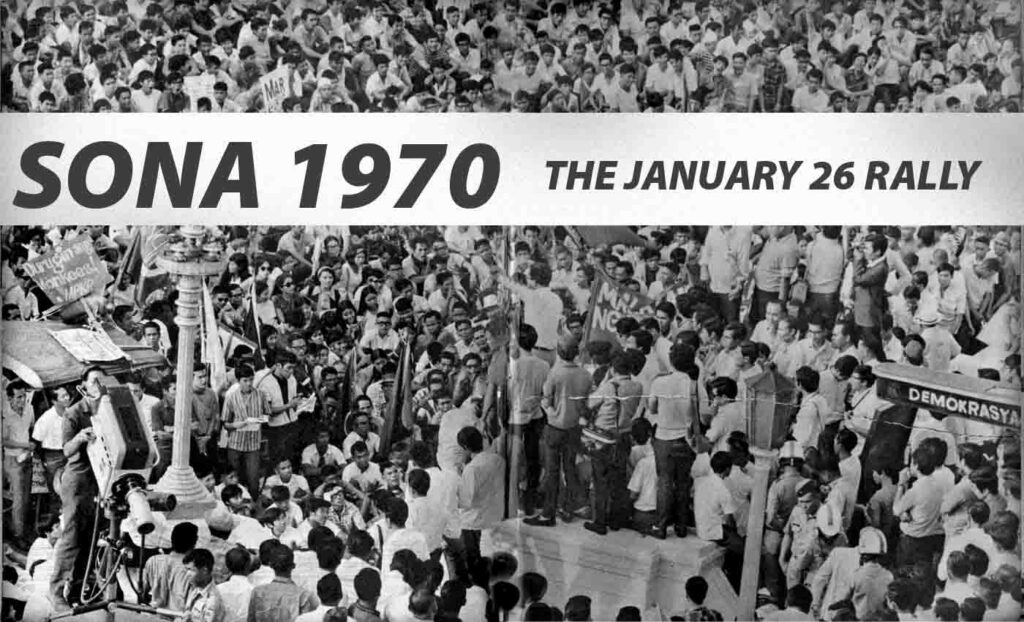

These series of events commenced on the 26th of January 1970, while President Marcos was delivering his annual State of the Nation Address (SONA) before the legislature, an estimated 50,000 protesters – mostly students – stormed the venue of the address. As the President was making his way back to his service vehicle, these demonstrators began throwing sticks and hurling at abuse at him, prompting riot police to subdue them by physical force.

The ensuing chaos left scores of protesters injured, including dozens of anti-riot police personnel, and the massive show of force by anti-government activists left President Marcos greatly unnerved. It is said that the heightening discontent with his administration, exemplified in the protests during the FQS, played a major factor in the dictator’s eventual declaration of martial law in 1972.

Many apologists of the Marcos regime would point to the escalating dissent as justification for the President’s proclamation of martial law, but those demonstrators had every reason to protest. It was in 1970 when major oil producing countries began hiking up their prices tremendously, this led to a flow-on effect that was damaging to net oil importing countries — such as the Philippines.

The rising price of commodities was strongly felt by the Filipino lower- and middle-income classes. In addition, taking advantage of the low interest rates in the global market the Marcos administration borrowed profusely to fund their large-scale infrastructure projects; it is noted that the Philippines’ foreign debt skyrocketed during this period.

As any keen observer of geopolitics would know, loans usually come with more strings attached than the interest rates imposed. It is believed by many observers of the Marcos era that the robust credit line afforded to President Marcos by the U.S. came at a cost of his country’s active participation in the Vietnam War.

From 1964 until 1969, thousands of Filipino troops would be sent to neighbouring South Vietnam to assist U.S.-led pro-Saigon forces. Although there would be no deployment of Philippine forces by 1970, the strategic port of Subic Bay was still widely utilized by American forces until the end of the war in 1975.

The worsening economy and President Marcos’ blatant servitude to the United States formed the basis of the growing discontent against his administration by progressive organizations. Thus a mass action was planned for the President’s SONA by student activist groups, calling themselves initially as the “January 26 Movement” but would drag on longer than that date alone.

Four days later, another mass protest action was conducted in front of Congress to condemn the brutal crackdown of protesters during Marcos’ SONA. This demonstration proved more intense than the previous, and the activists marched all the way towards Malacañang Palace — the official residence of the President.

This prompted police to violent disperse the demonstrators, including firing bullets at them, leaving four activists dead in its aftermath. The bloody crackdown would be remembered as the “Battle of Mendiola”, and would only further radicalize more student activists into rising up against the Marcos regime.

Until March that year, anti-government demonstrations would number to the tens of thousands. It was clear that discontent with the Marcos administration was reaching its peak, and the President – desperate to retain power – would see to it that he retains a firm grip on power, to a point where he descended into a full-blown autocrat.

Two years after the FQS, President Marcos declared martial law — effectively suspending democratic processes in the Philippines. It was a desperate ploy to maintain hold on power, utilizing the armed forces of the state to quell dissent and to silence opposition leaders.

Although he would remain in power until 1986, that was largely due to his authoritarian tactics that violently and lawless suppressed those who challenged his rule. While President Marcos maintained his hold on his office for the next sixteen years after the FQS, the disquiet he felt caused by the widespread demonstrations led to his unpopular decision-making that polarized not only the majority of the country but also his allies in the international community.

In summary, the FQS was the beginning of the end for the Marcos regime. From having been emphatically re-elected to a second term in 1969 due to his strong performance during his first term in office, the President was starting to see his fall from grace on that eventful day on January 26th, 1970.

Do you perhaps have a copy of the original article about the Battle of Mendiola? I’m doing a research about it and I need a primary source of article. Thank you ?