It has been 48 years since President Ferdinand Marcos placed the entire Philippines under martial law in 1972.

The decade that followed saw a brutal crackdown on activists, the persecution of Marcos’ political rivals, and the repression our most fundamental democratic rights.

Though martial law would be lifted by 1981, the dictator would remain in power until he was deposed by a popular uprising in 1986.

On the 21st of September every year, we commemorate the signing of Proclamation 1081 which placed the entire country under military rule. We also remember the atrocities of that era, vowing to resist tyranny and never allowing a repeat of those bloody martial law years.

Under the regime of President Rodrigo Duterte, the threat of martial law has never been more apparent. Reminiscent of the Marcos era, we are again seeing a systematic crackdown of activists, repression of political rivals, and attacks on the free press.

A research paper from Amnesty International (AI) states that over 3,200 people were killed during the martial law years, spanning a period of nine years from 1972-1981.

That number pales in comparison to the death toll recorded during the four years of Duterte’s reign as president thus far. The same Amnesty International report stated there had been 4,500 deaths related to his administration’s infamous “war on drugs” from 2016-2018 alone.

An investigation by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) reported that although they cannot ascertain the exact number of extrajudicial killings under the Duterte administration, the most conservative estimate – extrapolated from official government data – would peg the death toll at 8,663 since July 2016.

Both counts represent a higher death tally in a span of 2-4 years than the entire ten years of Marcos’ martial law. Even the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency’s (PDEA) own estimate of 5,722 drug war casualties dwarfs the death toll of the Marcos years.

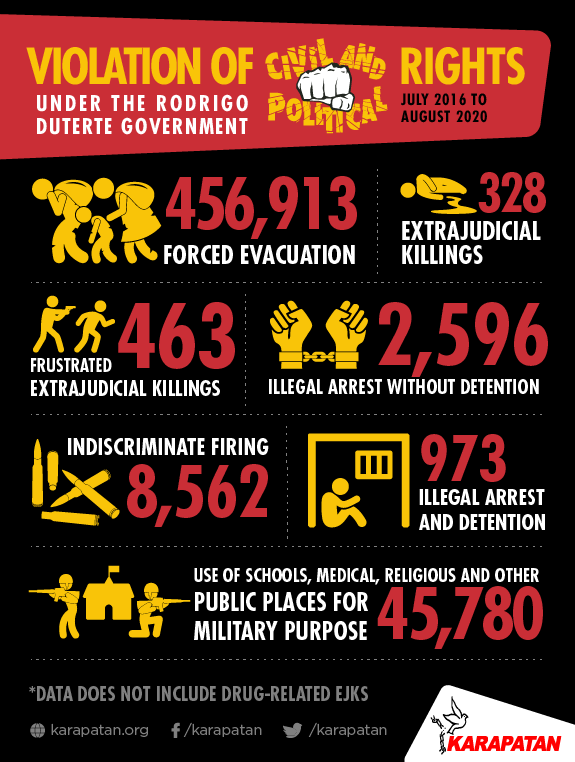

Political prisoners are not unheard of under the Duterte regime. Human rights organisation Karapatan stated that there had been 2,596 illegal arrests without detention and 973 illegal arrests with detention, under the present administration.

There have been notable examples: in April, volunteers from the peasants’ mass movement, Anakpawis, were arrested by police on their way to deliver humanitarian assistance to impoverished farmers hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These volunteers were apprehended at a police checkpoint and brought to a police station where they were detained without any explanation or charges.

In October 2019, seven human rights workers were arrested without a warrant in Puerto Princesa, Palawan. Combined police and military personnel apprehended the group and accused them of being in possession of firearms, a claim the social activists denied.

Even worse, one member of the group was accused of being a member of the underground guerrilla organisation, the New People’s Army (NPA). The arresting authorities justified their arrest without warrant, saying they were “prompted by information” given to them by an informant that a guerrilla fighter was present in the vicinity.

Perhaps the most prominent political prisoner under the Duterte regime is former Senator Leila de Lima, once seen as the President’s fiercest critic.

She was arrested and charged in 2017 over drug-related charges after pro-administration forces accused her of receiving bribes from drug lords.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) considered De Lima’s detention to be “politically-motivated”, calling charges against her “arbitrary”.

Both HRW and Amnesty International called for her immediate release from jail, with the former’s deputy director for Asia – Phelim Kine – saying the Senator’s arrest was meant “to vilify her for her strident and principled opposition to his murderous drug war”.

The most significant fact to take note of is that the total number of illegal arrests under the Duterte administration as of August 2020 (3,569) is already more than half of President Marcos’ 14-year tally (from 1972-1986) of 5,044.

Within four years Duterte has already rivalled the deposed dictator’s 14-year record, the speed with which he is illegally detaining critics and activists is concerning.

And all indications suggest that this campaign of human rights violations will only get worse with the passage of the Anti-Terrorism Law.

This draconian legislation gives unprecedented powers to the Executive branch, creating a new body called the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC) which is composed of sitting Cabinet officials.

The ATC has the ability to designate individuals as “terrorists” and be able to issue arrest warrants against them – an ability that only the judiciary should have in a democracy. This group of officials may also order surveillance against those who they have identified to be “suspected terrorists”.

The most concerning aspect of the Anti-Terrorism Law is that it broadens the definition of “terrorism” or of a “suspected terrorist”. Under the previous law which the ATL replaced, there was only one definition of “terrorism” but this new law has six.

Because of the widening scope of what it means to be a “terrorist”, the ATL has raised concerns among activist organisations that this law could be used against them.

Even before the passage of the bill, the Duterte administration already found ways to detain critics and activists under dubious circumstances – accusing them of being communist guerrillas or plotting to overthrow the government.

With the ATL enacted into law, it will make it easier for the Duterte regime to order the arrest or surveillance of activist groups who oppose them.

On the 48th anniversary of President Marcos’ martial law, let us remember the atrocities that occurred under his dictatorship and what happened as a result of him consolidating his control over the country.

In that same breath, let us also be cognisant of the glaring signs under the current Duterte regime of a return to the Marcos era. We are again seeing a crackdown of the political opposition, attacks on activists, and the rising number of extrajudicial killings.

What’s more crucial to recognise is that mechanisms put in place by the regime, such as the Anti-Terrorism Law, will only help further their agenda and have the potential to make the Duterte years even worse than the Marcos era itself.

Let the anniversary of martial law buoy us to be vigilant and to be vocal about our opposition to the growing authoritanism under President Rodrigo Duterte.