If we were to take anything out of TV3’s “Power Brokers Debate”, it was that ACT leader David Seymour and New Zealand First leader Winston Peters clearly dislike each other.

More than policy talking points, the highlight of the night quickly became the snide barbs each of the four party leaders present threw at each other – in particular, between Peters and Seymour. In contrast, the Greens’ Marama Davidson and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer of Te Pāti Māori were more amiable towards each other – seemingly teaming up against both their male counterparts instead.

Much of the acrimony evidently came from Seymour, lashing out at Peters for allegedly being untrustworthy and blamed him for past governments’ inability to find solutions to long-term problems. The ACT leader had previously stated that he would not work with NZ First and its leader in any future government arrangement, proving to be a headache for the opposition bent on dethroning the Labour-Greens government.

Although Peters and Seymour share a common goal in kicking the liberal left out of power, the latter has detested any coalition agreement that includes NZ First. In fact, one might even say that the ACT leader’s loathing of his NZ First counterpart is even greater than his distate for the incumbent government he is supposedly trying to dethrone.

Seymour’s continuous attacks against Peters and NZ First might be a head-scratcher for many, but it is not hard to understand why given the founding principles of the ACT party itself.

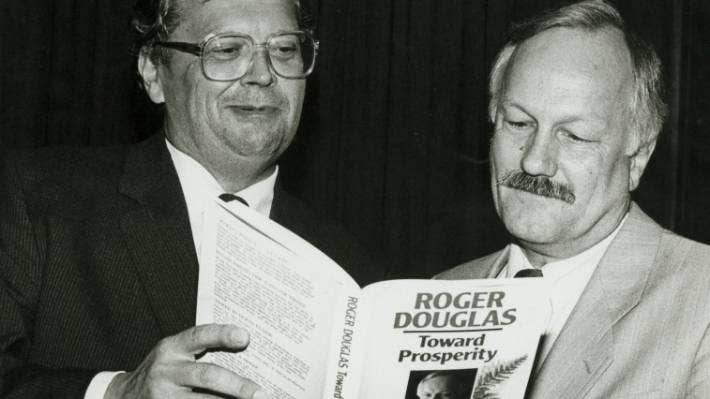

The Association of Consumers and Taxpayers (ACT) was founded in 1994 by Roger Douglas, the former Finance Minister of the Labour-led government of David Lange, which reigned from 1984-1990. Although coming from the centre-left Labour Party, Douglas often found himself as a pariah within the party given he was a staunch liberal, in both social and economic senses.

Douglas was behind the cruel neoliberal reforms of the Lange government, which introduced harsh austerity measures to New Zealand that included the introduction of new taxes, the laying-off of thousands of public service workers, and the privatization of numerous state-owned assets that were still generating dividends to the New Zealand government.

It was under Douglas’ policy direction that the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced in 1986, which imposed an added cost to the price of goods and services enjoyed by New Zealanders. This new tax was designed to plug the revenue gap created by the reduction of personal income tax rates – which ultimately benefits high-income earners.

Thanks to Roger Douglas, everyday Kiwis faced higher costs at the supermarket, at the petrol station, or with their rent while the highest-earning individuals could keep more of their money. The tax reforms of the 1980s saw the top marginal income tax rate drop from 66 per cent to a mere 33 per cent.

Future New Zealand governments would also suffer from the loss of various state-owned assets, many of which were generating dividends for the government, and even if they were not their sale still resulted in the loss of control for the government in how accessible these assets were to the New Zealand public.

Among these assets sold were the New Zealand Forest Service, which oversaw the country’s forestry sector. The sale of the Forest Service saw large tracts of forest land sold to private interests, effectively making the New Zealand government powerless in deciding how our forests were to be utilised.

The postal service was also reformed for the worse, as New Zealand Post was forced to “corporatise” itself. What should be a public service that allows Kiwis to communicate and connect with each other became a corporate entity designed to create profits.

Before the changes, NZ Post had a monopoly on postal mail in the country but in order to prepare for its privatization the Douglas-led Cabinet of Prime Minister David Lange gradually reduced its monopoly, weakening it as a state-owned asset. From 1987 to 1988, it is believed that the postal arm of NZ Post lost approximately $50 million.

Other publicly-owned entities that were privatised were New Zealand Steel, which was an industry that made the country self-sufficient in producing steel – providing a more secure building sector. As well as Air New Zealand, which effectively meant the country’s flagship carrier was no longer owned by the Kiwi public.

Roger Douglas’ Labour government can be summarised in two broad themes: the imposition of new taxes on middle-class and working class New Zealanders to pay for tax cuts for wealthier Kiwis, and the loss of state-owned assets that not only provided the New Zealand government with revenue, but were also treasured heirlooms that future Kiwi generations could have been proud of.

Collectively, these harsh neoliberal reforms would later be dubbed as “Rogernomics”, and became the foundation of Winston Peters’ entire political career, even up to this day.

It was Peters, who was seen as a protégé of former National Party Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, who vociferously objected to these neoliberal reforms. When the National Party dethroned David Lange in 1990, it was again Winston who vocally criticized his party leader Jim Bolger’s reluctance to reverse many of those neoliberal reforms – eventually resulting in his sacking from the latter’s government, in 1996.

It was after Peters got sacked from Bolger’s neoliberal government that he set up New Zealand First, which since then, has been the only party that has consistently opposed neoliberalism, the sale of state-owned assets, and economic liberalisation.

It should be no surprise then that Seymour, as the incumbent successor of Roger Douglas, has so much vitriol towards Peters. The latter will become a robust barrier between a government with ACT in it, and further neoliberal reforms.

We are already hearing from National and ACT that they will overturn the ban on foreign buyers buying New Zealand houses, a phenomenon which greatly inflated house prices pre-2017. The ban was introduced when NZ First was last in government in 2017.

Seymour has also voiced his desire to raise the retirement age, which means Kiwis will be working longer before they can enjoy their retirement. Meanwhile, Peters and NZ First have long held superannuants as one of its core constituencies.

ACT and National’s plans to further lax immigration rules, opening the floodgates for more migration into New Zealand, is also incongruous with NZ First’s long-held stance on sensible immigration.

In short, Seymour and the liberal ACT party find it extremely unfathomable to work with Peters and NZ First because the latter party and its leader will prove to be a tough roadblock for any further liberalization of the economy, any further attack on workers and wages, and any plans to sell-off more of our state assets.

Unfortunately for Seymour, neither he nor Christopher Luxon will be deciding the next government – that will be up to the voters – and a vast number of Kiwis will not be keen to see their country’s sovereignty, their children’s future, and the treasures we have inherited from past generations be trampled on again.