Very few political polls command the same fanfare and intrigue as 1News’ Kantar Public Poll, the only exception being the Newshub-Reid Research Poll.

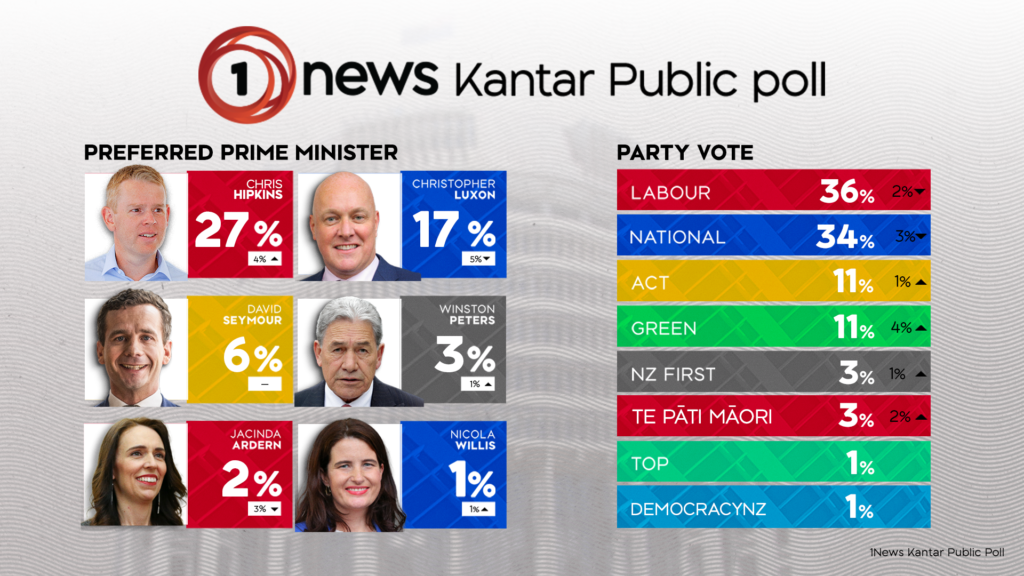

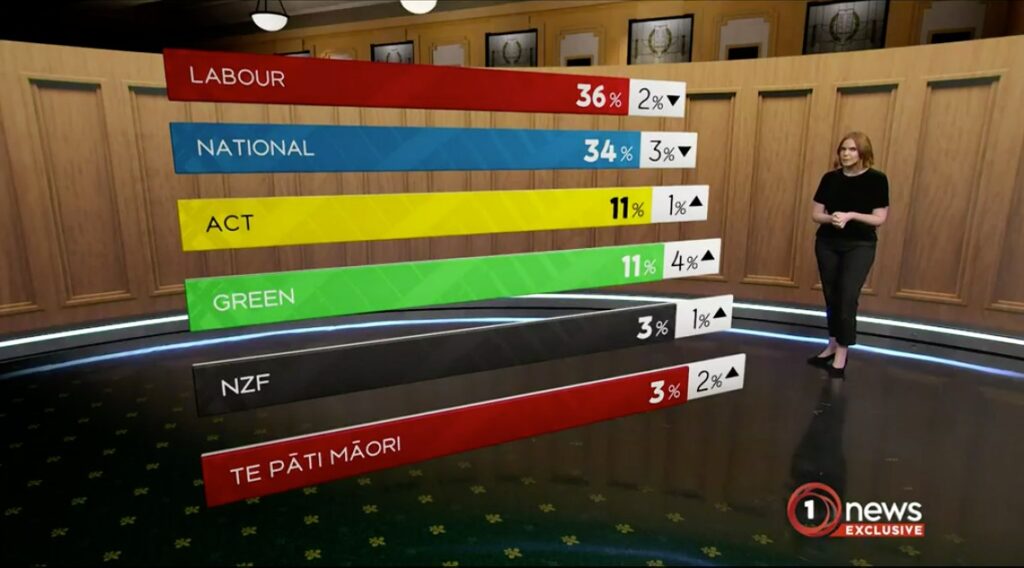

Thus, when the latest 1News poll came out Monday night the spotlight was on either one of two things: that Labour and the Greens could form a government with Te Pāti Māori, or that Christopher Luxon – once touted to be the National Party’s saviour – has plummeted in the preferred Prime Minister polls while the incumbent, Chris Hipkins, soared.

But there was one aspect of the latest 1News poll that has largely gone unnoticed or has flown under the radar of even keen political observers: that the balance of power could fall either to Te Pāti Māori or New Zealand First, each registering three percent of the party vote in the poll.

NZ First and TPM are as much alike as they are different: both are political parties with a large following from Māori voters, especially outside the Big Three cities. At each of their helm are recognisable Māori male leaders, Winston Peters and Rawiri Waititi respectively.

Ironically, the core of their respective political philosophies could not be further apart: while TPM advocates for Māori sovereignty, self-determination and upholding the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand First champions a unitary nationalist identity, refusing separate recognition of Māori people under New Zealand law, guided by the principle of “one law for all”.

It is poetic that the task of forming the next government could fall to either one of those two parties. If polling numbers continue trending this way, the issue of co-governance and what the Treaty of Waitangi demands of present-day New Zealand will be the top issue on most voters’ minds.

If Te Pāti Māori end up taking part in coalition negotiations, it is certain that furthering co-governance within Government entities will be one of their key demands.

Co-governance has become a point of contention among New Zealand voters during this term of government. Put simply, it means ensuring that Māori iwi have equal decision-making powers as Crown representatives in managing key natural resources.

This is manifested in guaranteed seats for iwi representatives on governance boards of Crown entities, and was a flashpoint in the highly contentious Three Waters reform that then-Local Government Minister Nanaia Mahuta spearheaded.

As part of the Three Waters plan, mana whenua are guaranteed equal representation with local councils in a top-tier governance group overseeing our water infrastructure. While the board will be tasked with operational management, they will not have operational authority.

So unpopular was this plan that it eventually led to Mahuta losing her Ministerial portfolio of Local Government, which was widely seen as a demotion on her part.

The divisiveness of the Three Waters plan was also seen as a large reason why Labour lagged in the polls to National. It did not come as a surprise then, that Hipkins sent the Three Waters plan back to the drawing board when he took over as Prime Minister early this year.

Te Pāti Māori also withdrew their support for the Three Waters reform, but for a different reason – they felt the fine details of the program did not implement co-governance principles enough.

When Hipkins announced the deferral of the Three Waters reform, Te Pāti Māori co-leader Debbie Ngarewa-Packer expressed her “shock” and “dismay”. She allayed fears that Hipkins’ government will “slow down” co-governance efforts, saying: “It’s disappointing when we see ourselves being shelved”.

By ‘we’, Ngarewa-Packer means the Māori people who she claims were being neglected in the new Prime Minister’s policy reprioritisation. Such is her party’s determination to maximise the potential of co-governance between iwi and the Crown that she would weaponise her Māori identity to galvanize support from Māori people for her party.

With this, it is quite clear that if they found themselves in a position to form the next government furthering co-governance will be a key Te Pāti Māori demand.

Contrast that to the other party in a likely position to be “kingmaker” – New Zealand First.

Its leader, Winston Peters – a revered Māori leader himself – has consistently opposed what he calls “separatism”, that is treating Māori as separate to other New Zealanders of non-Māori descent.

The antidote to “separatism”, according to NZ First, is the principle of “one law for all” – whereby all New Zealand citizens are bound by the same treatment and recognition under the law. The concept of co-governance would be incongruous with this principle.

If polling numbers hold steady, and the role of kingmaker looks likely to fall with either NZ First and TPM, the issues of co-governance and separatism will dominate the political airwaves and the 2023 general elections will become a referendum on co-governance.