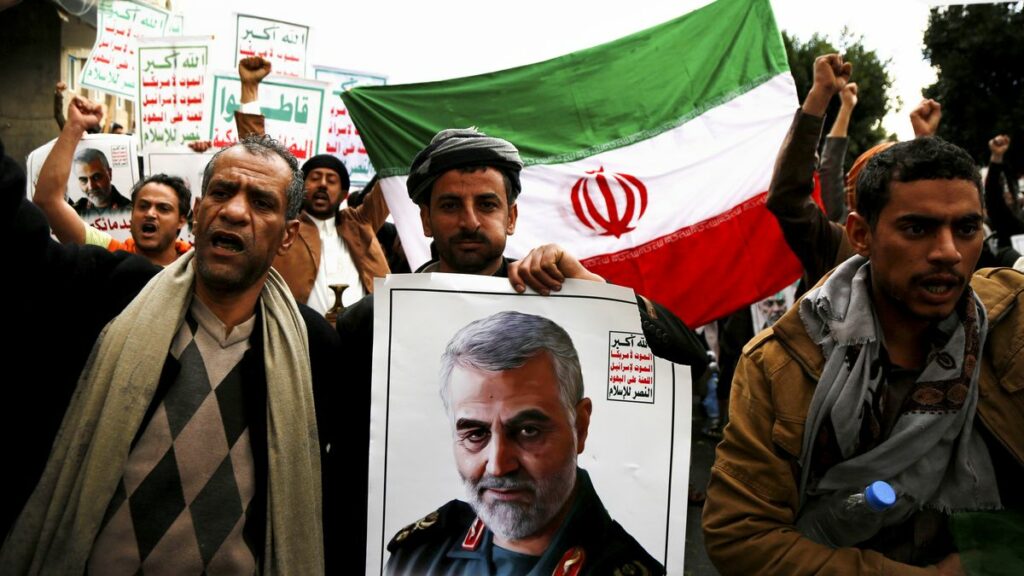

Since the beginning of the Trump Presidency, the Islamic Republic of Iran has been treated as public enemy number one in the eyes of the United States. That animosity reached its boiling point at the start of the new year, with an American drone successfully assassinating acclaimed Iranian general – Qasem Soleimani – in Baghdad, and with Iran retaliating by launching a barrage of missiles into U.S. forces stationed in Iraq.

Though tensions may be exceptionally high during the past week, confrontation with the U.S. – or even the West in general – is nothing new for Iranians. In fact, their country’s current political system – a theocracy where a cleric, the Ayatollah, is Supreme Leader of the land – is indirectly caused by past foreign policy decisions of the U.S. and the U.K.

When asking an American’s point-of-view of U.S.-Iran relations, they are most likely to point to the 1979 Iran hostage crisis – when dozens of American nationals were held hostage at the U.S. embassy in Tehran – by radical student activists as the start of the two countries’ feud. However, to fully understand why the hostage situation occurred to begin with and to fully appreciate Iranian animosity towards the American state, one must look further back to the year 1953.

Mosaddegh, Iranian nationalism, and the Abadan Crisis

In 1951, an academic by the name of Dr. Mohammad Mosaddegh was appointed as Iran’s Prime Minister after winning a popular vote in the country’s parliament. A staunch nationalist, Mosaddegh sought to properly manage Iranian oil reserves to benefit his people more which at that time was under the dominant control of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC; later known as British Petroleum or BP).

The Prime Minister saw AIOC as the foreign arm of the British Empire, while Iran was not a colony of the United Kingdom many Iranians felt they were under the dominion of the Empire — especially when it came to their massive oil wealth. In Stephen Kinzer’s book, All the Shah’s Men (2008), he states that there was “widespread political dissatisfaction with the royalty terms of the British petroleum concession” whereby Iran only received 16 per cent of net profits from oil exports.

Mosaddegh sought to rectify this travesty and in 1953 sought to nationalize his country’s oil. The AIOC’s concession to extract oil from Iran would have ended in 1993, but the nationalist president revoked it abruptly – citing its perceived unfairness – and expropriated their assets.

At the stroke of Mosaddegh’s pen, the Iranian people became the sole proprietors of their country’s oil reserves. This earned the ire of AIOC, and by extension the British Empire, who then plotted to remove the Prime Minister from power and ensure the future of their oil revenues.

This sparked a series of event known in history as the Abadan Crisis, named after the Abadan Oil Refinery in Iran which was one of the AIOC assets nationalised by the Mosaddegh government. In 1952, the British oil company – supported by their British government, led by then-Prime Minister Winston Churchill – instigated a worldwide boycott of Iranian oil exports as retaliation for the Iranian government’s abrupt nationalisation of their oil reserves.

Operation Ajax/Operation Boot and the Fall of Mosaddegh

By early 1953, Iranians were suffering from the boycott of their main export with their economy in the gutter. Capitalizing on this discontent, the Churchill government would orchestrate a coup in Iran with their American allies – then under the Presidency of Dwight Eisenhower – to remove Mosaddegh from power, and replace him with Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi — Iran’s monarch who was distrusted by the people due to his close ties with the West.

While the Shah was the de jure head-of-state of Iran, it was Mosaddegh who enjoyed support from the people. The two constantly struggled for power, until they reached a breaking point on July 16, 1952 when a War Minister nominated by the Prime Minister was rejected by the Shah, which led to Mosaddegh abruptly resigning from office, sparking mass protests on the streets against Pahlavi.

After six days, fazed by the mass dissent, the Shah backs down and allows Mosaddegh to form a government of the latter’s liking. A weakened Shah was bad news to the Western imperialists, thus not long after the Prime Minister’s victory Churchill would tap the help of Eisenhower to plot a regime change in Iran.

Shortly after, Operation Ajax – the CIA codename for the plan to bring down Mosaddegh – or Operation Boot (for the British MI5) was put into place. But the (initial) execution of the coup plot would fail: in August 1953, a royal decree signed by the Shah would replace Mosaddegh with General Fazlollah Zahedi – a loyalist of the Iranian monarch.

The decree was given to Colonel Nematollah Nassiri of the Iranian Imperial Guards to be enforced, but pro-Mosaddegh forces learned of this plan beforehand and surrounded the Prime Minister’s living quarters on the night of the proposed coup. Civilian supporters of Mosaddegh also trooped to the streets as news of an attempted coup spread throughout the country, and this backlash forced the Shah to flee Iran and seek asylum in Rome.

However, anti-government mobs also ran riot in Iran calling for the resignation of Mosaddegh. This culminated in what was known as, “The Decisive Day”, when civilians and military forces loyal to the Shah confronted pro-Mosaddegh soldiers guarding the Prime Minister’s living quarters, resulting in a bloodbath.

In the aftermath, more than 300 people were dead including civilians. The pro-Shah forces backed by tanks gained the upper hand against Mosaddegh’s troops, successfully arresting the Prime Minister on the 20th of August 1953 — this marked the end of the Mosaddegh government.

U.S. admission of involvement in 1953 coup

It wasn’t until 2013, the 60th anniversary of the coup, did the U.S. finally admit their involvement. Declassified documents from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) revealed that they orchestrated an elaborate plan to overthrow Mosaddegh, including the bribery of Iranian public and military officials and the dissemination of anti-Mosaddegh propaganda which was vital in mobilizing pro-Shah mobs onto the streets.

The declassified documents also revealed that the British government sought to stop the CIA from making this information public since it revealed their involvement in the coup also. Britain, and in particular their foreign secretary Sir Anthony Eden, regarded Mosaddeq as a serious threat to its “strategic and economic interests” after the Iranian leader nationalised the AIOC.

Abbas Milani’s book, The Shah (2011), said that in return for American help in toppling Mosaddegh the latter had required the removal of AIOC (or BP’s) monopoly over Iran and allow the entry of five U.S. oil companies. The Prime Minister’s ouster also paved the way for Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to return to power and rule Iran unilaterally until 1979.

Resentment of the Pahlavi dynasty

For the same reason he was unpopular before the coup, the Shah’s favour with the Iranian people gradually waned. He was seen by his people as being to close to the West, and given the true ramifications of Mosaddegh’s ousting became apparent to most Iranians that was a bad thing.

It should be noted that Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s predecessor and father, Shah Reza Pahlavi, was also deposed by Western powers. During the Second World War, the U.K. and Soviet Union invaded Iran in 1941 – despite the country declaring itself neutral during the war – as they felt that it was too friendly to Nazi Germany; thus, there had been two Iranian leaders removed by Western imperialists in the 20th century alone — earning the ire of its people.

Given that Shah Mohammad Reza’s position was bestowed on him by the workmanship of the West, many Iranians expected the monarch to be beholden to Western powers in the future — and they were not wrong. The Shah begun a series of radical reforms in 1963 called, the “White Revolution“, and begun liberalizing the Iranian economy to open up trade with the West.

The Shah also lived a lavish lifestyle, residing in the luxurious 27-acre Niavaran Palace in Tehran. He was fond of opulent banquets, and when he celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire he flew in dozens of world-class chefs from Paris and invited the heads-of-state and monarchs of the world.

The Iranian monarch also boasted a collection of Cadillacs, Italian-tailored suits, while his twin sister – Ashraf Pahlavi – was the proud owner of a lush eight-story mansion in Manhattan, in the U.S. The Pahlavis’ affluence was a slap in the face of most Iranians, who were still reeling from the global oil boycott of the past and now the liberalization of the economy by the Shah.

The Rise of the Ayatollah

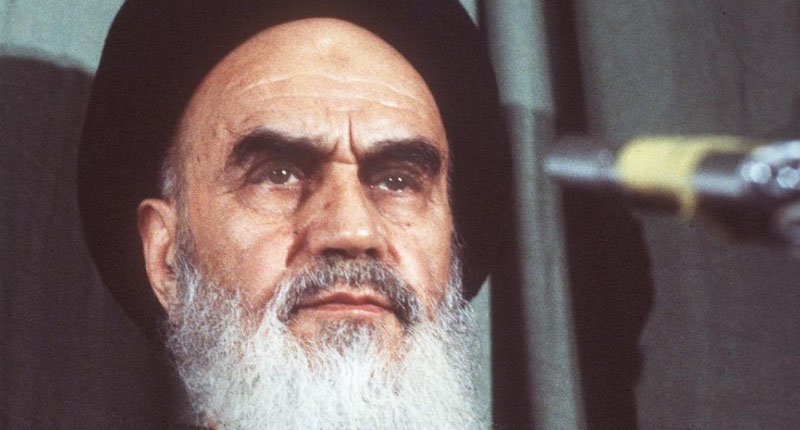

One of the many opponents of the Shah was a religious cleric named Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who publicly lambasted the White Revolution, saying it aimed to “bolster foreign influence over Iran”. He said that the reason it was called the “white” revolution is because the orders came directly from the American White House, Khomeini would later be arrested for being a fierce critic of the Shah.

Khomeini was a Shi’a ayatollah, or a high-ranking cleric of the sect, and was against the White Revolution’s social reforms, which he perceived as the “westernization” of Iran by the Shah. He opposed the modernization of Iran’s social values, particularly bestowing women the right to vote, saying it “eroded the country’s Shi’a traditions”.

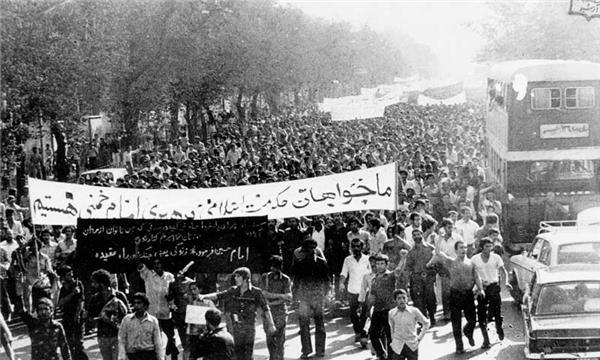

The Ayatollah’s imprisonment emboldened many religious Shi’a to rise up against the Shah, beginning in the city of Qom — the site of great religious significance for the Shi’as and where Khomeini was based — but quickly spreading to other cities also. Pressured by the religious cleric’s clout with many Iranians, the Shah granted Khomeini his release from prison but was sent into exile in Iraq for the next 15 years.

Iran’s monarchy had become authoritarian, many political opponents would be imprisoned, assassinated, or disappeared — most likely by the handiwork of the SAVAK, the Iranian secret police that received training from the CIA and the Mossad of Israel. The SAVAK became widely feared in all of Iran and further added to the resentment of ordinary Iranian citizens towards the Shah.

The rebuke of the Shah led many to support the Ayatollah, as the cleric quickly became the leading opposition figure against the Iranian monarch. Even from his exile in Iraq, Khomeini’s influence helped plant the seeds of defiance that would bloom into a revolutionary movement by the late 1970’s.

As Iranian discontent was nearing its climax, all that’s left was a spark to ignite a final blow to the Shah. This came in the tragic 1978 Rex Cinema terrorist attack, when four arsonists set a movie cinema full of people ablaze — killing 422 in the process.

Outraged by the deliberate act of violence, the Iranian public erupted in mass protests and turned their anger to the Shah convinced it was his covert SAVAK operatives that perpetrated the crime — although this was never substantiated. The demonstrations grew larger and became fiercer, ultimately forcing the Shah to cede power to a caretaker government in late 1978.

On the 16th of January 1979, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled Iran — it was the end of the monarchy. Ayatollah Khomeini returned to his home country from exile on the 1st of February that year and became the de facto new head-of-state; but it wasn’t until April did Iranians vote to become an Islamic Republic, with Khomeini rising as the official leader, becoming Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Iran formally becoming the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Lessons for today

Those events in early 1979 brings us to where Iran is at present, a theocracy – ruled by a religious leader, the Ayatollah – which holds deep animosity and skepticism towards the U.S. and the rest of the Western powers — and for good reasons. What started as a dispute over oil would spark a series of events that transformed a once secular nation, albeit a flawed democracy, into an autocratic, theocratic state — where individual liberties are severely curtailed.

The Western powers painted Prime Minister Mosaddegh as an evil that had to be removed, but the blow-back resulted in arguably one of the most illiberal states in the world. Present-day Iran, a theocratic state, poses problems for international affairs but we must remember that this reality was caused by the imperialist greed of the West.

Just as the United States made the fatal mistake of propping up the fundamentalist group, Taliban, in Afghanistan to combat the expanding Soviet forces, only for that group to turn against them and becoming a problem to international security themselves, so too did they – along with the U.K – make the same error by driving out Mosaddegh to support the Shah.

The former was a believer in transforming Iran into a modern, secular society himself which normally would gain the support of the West, but because he (rightfully) clung to the idea that the Iranian people be the proprietors of their land’s natural wealth — the imperialists removed him from office. Today, the U.S. is struggling to keep Iran in check but they can only blame themselves on why the Iranians are uncooperative with them to begin with.

References:

- Milani, A. (2012). The Shah. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mosaddegh and the coup d’état of 1953 by Mohammad Homaeefar

- Kinzer, S. (2003). All the Shahs men: the hidden story of the CIAs coup in Iran. New York: Wiley.