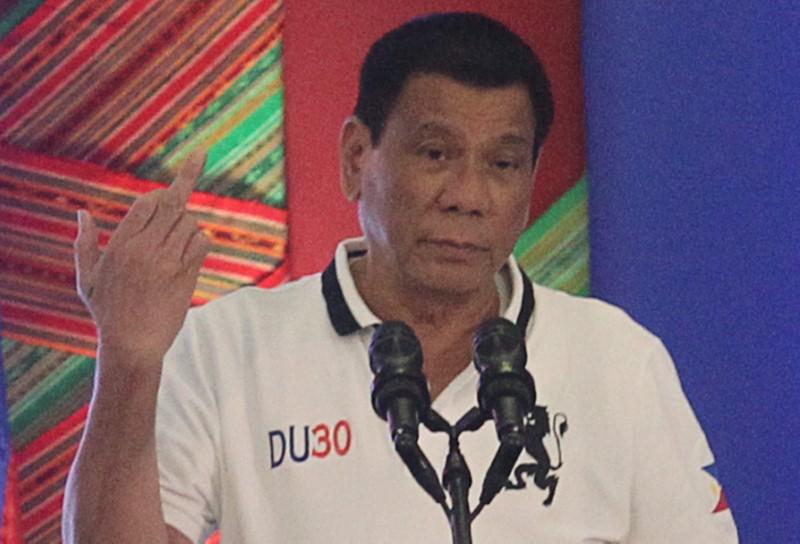

In a rare occasion, human rights groups, church leaders, showbiz celebrities, school administrations, and even global pop star Taylor Swift herself are uniting to criticise the government of President Rodrigo Duterte.

Usually it is only the activists from progressive organizations, church groups, and student activists who voice dissent against the administration. But the gravity of this bill, that only lacks the President’s signature before becoming a law, is so serious that nearly every sector of Philippine society has been put on notice.

But what is the fiasco about and is everyone justified to be up in arms about it?

[READ THE FULL TEXT: Senate Bill 1083]

The purpose of this new bill is to give law enforcement authorities “more teeth” to deal with terrorism and to “pre-empt acts of terror“, to prevent similar scenarios as the 2017 Marawi Siege from happening. Even though that surprise attack by Islamic State militants two years ago was largely due to the deficiency in intelligence gathering by the Philippine Military, the Duterte administration believes this new law is necessary.

Critics of the proposed law argue that there are already ample provisions stated in the Human Security Act of 2007 to combat terrorism. That law passed by former President Gloria Arroyo was also widely criticized for giving the state draconian powers, but human rights organizations are more worried about this new bill.

For a start, SB 1083 creates a new body called the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC), comprised of Cabinet officials, who will be responsible for the implementation of the new law (Section 53). Section 29 of the bill empowers the Council to order the arrest, detention, or surveillance of individuals they suspect to be engaging in terrorist activities.

The notion of Cabinet officials, who belong to the executive branch, giving arrest or surveillance orders to law enforcement agents is baffling given that the Philippine Constitution specifically mandates the separation of powers. How can members of the executive perform functions Constitutionally-reserved for the judiciary?

To pacify terrorist activities, the Anti-Terrorism Bill gives law enforcement authorities the power to detain suspected “terrorists” for up to 14 days without an arrest warrant; this can be extended by 10 days if deemed necessary (Section 27, page 26, line 2). Already, this provision is problematic because under the Constitution no one can be detained for more than three days without being charged for a crime (Article 7, Section 18) – even during the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

SB 1083 also allows the police or military to place suspected individuals under surveillance for a period of 60 days, which can be extended to a further 30 days if they need to do so. Again, the wording used is “suspected” – which leaves a great deal of people exposed to having their privacy breached if the ATC suspect them to be terrorists.

What makes the word choice “suspected” even more deplorable is that it directly contradicts one of the most fundamental legal principles, the presumption of innocence. This dictates that any suspect should be regarded as innocent until proven guilty, but under the Anti-Terrorism Bill someone could be seen as guilty of a crime under the direction of the ATC.

What will stop members of the ATC from using their powers against critics or their political rivals? The loose wording of the Bill allows for grave abuses of power to occur, a feat that is not unheard of under the Duterte regime.

In the past four years of President Duterte’s reign, we have seen many activists who have faced prosecution or worse, assassinated, after being accused of corroborating with “terrorist” groups. It can be remembered that only in 2018, the administration accused more than 600 individuals – including a United Nations special rapporteur – of allegedly being involved with terrorist activities.

Thankfully, courts would later dismiss these charges citing lack of evidence. But the incident made it clear that the Duterte government uses the “terrorist” label very loosely; the 649 who the Department of Justice (DOJ) wanted to label as “terrorists” two years ago all had one feature in common among them – they were all critics of the President.

![Activist groups stage a protest rally in front of the Philippine National Police headquarters against the Anti-Terrorism Bill. [Photo from Karapatan]](https://thedefiant.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PHL_AntiTerrorBillKArapatan_Karapatan.jpg)

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of the Anti-Terrorism Bill is its timing: on the 1st of June, protests erupted around the nation’s capital, Metro Manila, due to restrictions placed on public transportation. Shortly after, President Duterte certifies the Anti-Terrorism Bill as “urgent” thereby expediting its passage through the legislature.

Failing to stymie the spread of COVID-19 in the Philippines, the Duterte government faced mass unrest and quickly sought to give themselves more powers to quell any dissent. Therefore it begs to be asked, is the purpose of the Anti-Terrorism Bill to protect the populace from “terrorism”, or to safeguard the administration’s hold on power?

If passed into law (which is inevitable now given the bill only requires the President’s signature) the Bill will put activists and those who protest the government’s policies under the mercy of an elite group of Cabinet members. This is as good of a reason as any to be worried about the Anti-Terrorism Bill and why we should valiantly oppose its passage into law.

![Activist groups stage a protest rally in front of the Philippine National Police headquarters against the Anti-Terrorism Bill. [Photo from Karapatan]](https://thedefiant.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/PHL_AntiTerrorBillKArapatan_Karapatan-715x400.jpg)

5 thoughts on “Philippines: What is the “Anti-Terrorism” Bill and should we be concerned about it?”

Comments are closed.