A prevalence of serious crimes has renewed calls to reinstate the death penalty in the country.

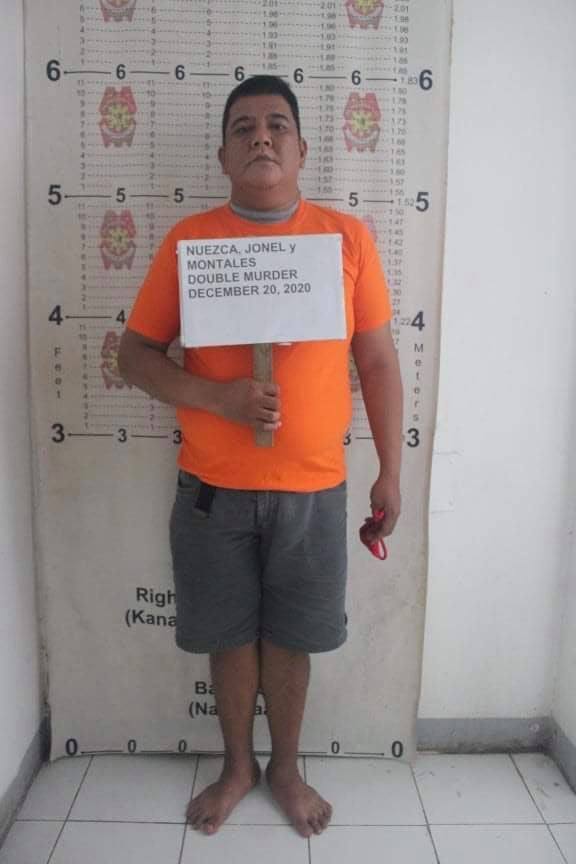

The nation was up in arms over the double murder of a mother and her son by an off-duty police officer caught on video late last month. A week earlier, a health worker and her husband were both shot dead by an unidentified assailant in Guihulngan City.

Beyond violent crimes, widespread anger remains over government corruption. The reported corruption inside PhilHealth, the state-owned insurance company, amidst a pandemic has pushed for calls to sentence plunderers to death.

The pervasiveness of injustice has stoked the appetite of Filipinos to revive capital punishment in the Philippines. To them, criminal acts have become rampant because criminal minds are no longer afraid of facing the law.

As is the most common argument in favour of the death penalty, proponents believe reinstating it will deter crime. But on the contrary, doing so will only aggravate injustice in the country.

Studies in the United States (where the death penalty exists in several states) have shown no evidence that imposing capital punishment actually discourages crime. States which did record falling crime rates already observed the trend before they adopted the capital punishment.

Penologists have also found that the certainty of conviction and punishment is a more potent deterrent to crime, rather than the severity of the punishment.

This makes sense, after all even if the death penalty was available a person will still need to be convicted first.

If your justice system is prone to favouritism, wherein the highly-influential and well-connected regularly avoid conviction, they can easily avoid capital punishment.

Inversely, this would mean that the ordinary citizen – those who do not have deep pockets to bribe the courts or have friends in high places – will be at a disadvantage. It is no surprise therefore that the death penalty is often considered anti-poor.

Robin M. Maher, former director of the American Bar Association (ABA) Death Penalty Representation Project, argued that “poverty is both a personal characteristic and a risk factor” with the death penalty.

“Without resources, poor people accused of serious crimes cannot retain skilled and effective lawyers to present an adequate defence,” Maher said. Lacking such resource, “a death sentence is an often a foregone conclusion”, she added.

In the Philippines, there is no shortage of examples of the rich and powerful evading justice, while the poor end up on the receiving end of punitive actions.

Former First Lady Imelda Marcos was sentenced to decades in prison in 2018 for multiple counts of graft, stemming from a case wherein she illegally funnelled about $200 million to Swiss foundations in the 1970s as Metropolitan Manila governor.

But despite being convicted of a serious crime – government corruption – a crime which majority of Filipinos purportedly loathe, the deposed dictator’s widow is yet to spend a single day in a prison cell.

The treatment law enforcers afforded Mrs Marcos was in stark contrast to the fate of another senior citizen caught shoplifting years ago. In 2012, a 79-year old man was arrested for stealing a small bag of chocolates from a supermarket.

Unlike Imelda who was convicted of stealing millions, the geriatric shoplifter’s total haul amounted to a measly Php36. But the man’s punishment far exceeded that of the former First Lady’s: the supermarket owner pressed charges of theft against the senior citizen and was detained at a Manila Police District station for several days.

The glaring discrepancy in how the two individuals were treated demonstrates how uneven the Philippine justice system is: it is a broken system that is skewed to favour the rich. Adding the death penalty into the equation will only worsen the injustice committed.

It is an open secret that the wealthy and influential are “untouchables”, who are able to elude justice with ease. Creating a more punitive punishment such as the death penalty will not deter them, as they know they can easily evade conviction.

Hence, not only will the poor be at greater risk of state-sanctioned execution it is also highly unlikely that well-connected criminals – especially those who come from powerful dynasties – will ever be meted out the death penalty. This only worsens injustice in the country.

The escalating lawlessness in the country is not due to the lack of punitive punishments, but because of the inability of those in power to be brought to justice.

When you know you’re immune to prison because of your last name, or who you know, or who you’re related to, there is no deterrent for you to commit atrocities – regardless of what the maximum penalty available may be.

Thus, reintroducing capital punishment will prove futile in stemming serious crimes. In fact, it will only magnify the injustices in our country because our unfair judicial system will ensure that only those who cannot afford a robust legal defence or who know people in high places, will be meted out with this punishment.

What we require is a fundamental reform of our justice system and to ensure that one’s privilege does not act as an extenuating circumstance to sentencing.